You get what you need

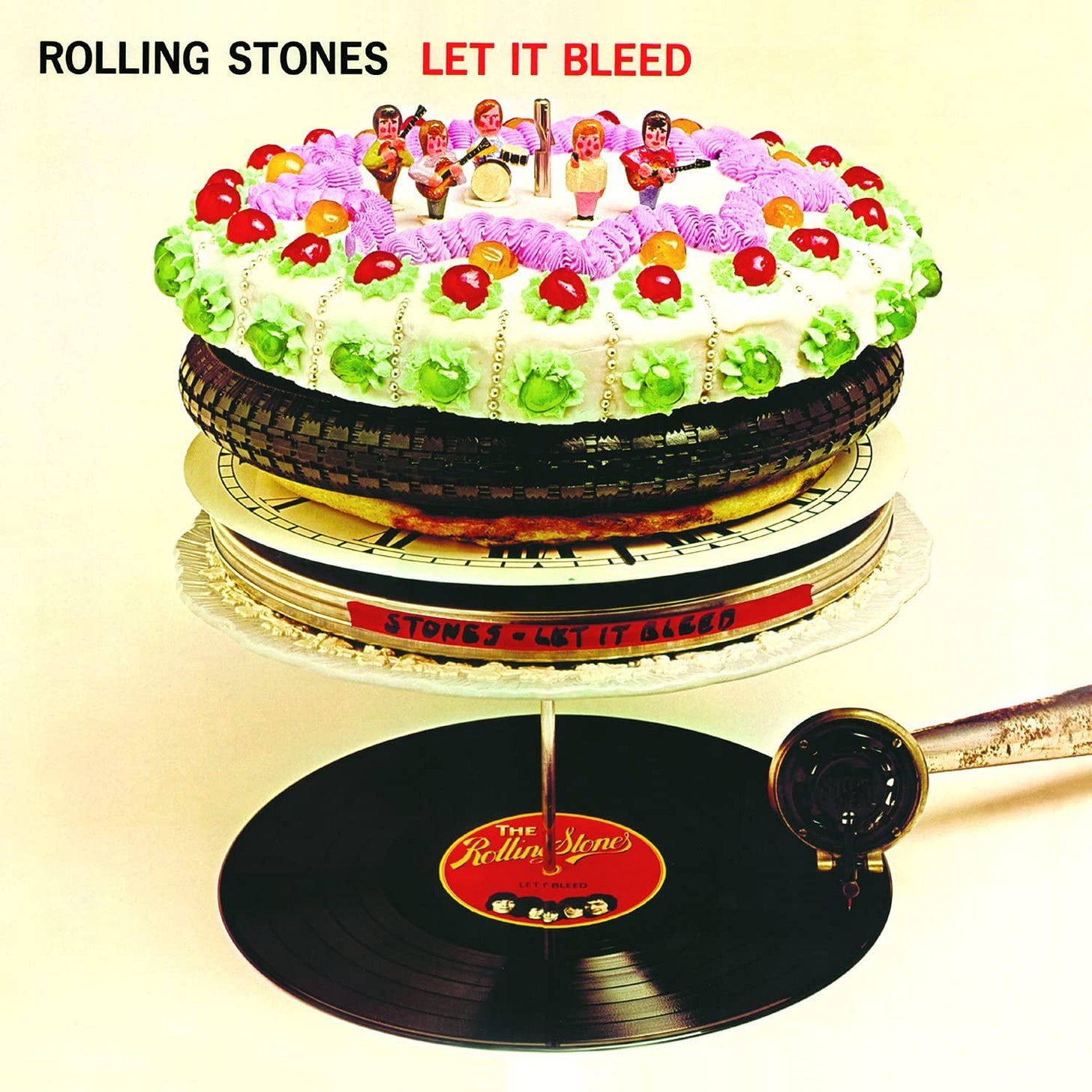

The Rolling Stones - 'You Can't Always Get What You Want' (Let It Bleed - 1969)

It is 8th August 1968, Mick Jagger has flown back into London, and he is heading to a party where the seventh album by The Rolling Stones,1 Beggars Banquet, will be showcased to the lucky people in attendance. Recording on the album finished in late July, and the record would come out in December that year. People are into it; they are jumping and dancing to it - I’m sure ‘Sympathy For The Devil’ and ‘Street Fightin’ Man’ go down well.

Keith Richards’ assistant, Tony Sanchez or Spanish Tony as he was also known, was in charge of the sound system that night. One of the guests approached him with a similarly new and fresh record that his band had finished recording mere days earlier. That guest was Paul McCartney. - “See what you think of it, Tony; it’s our new one”, he allegedly says.

Keith Badman quotes Spanish Tony in his book The Beatles: Off the Record, released at the turn of the century;

I stuck the record on the sound system, and the slow thundering build-up of ‘Hey Jude’ shook the club. I turned the record over, and we all heard John Lennon’s nasal voice pumping out ‘Revolution’. When it was over, I noticed that Mick looked peeved. The Beatles had upstaged him.

He goes on to say that Paul McCartney’s recollection was that;

I remember Mick Jagger coming up to me and saying, ‘F*ckin’ ‘ell! F*ckin’ ‘ell! That’s something else, innit? It’s like two songs.’

That comment on ‘Hey Jude’ being like two songs is fascinating. Jagger elaborated on this in 1969 when he said;

I liked the way the Beatles did that with ‘Hey Jude’, The orchestra was not just to cover everything up—it was something extra. We may do something like that on the next album.

The Rolling Stones had dabbled with orchestral backing before 1968; you can hear that on ‘She’s A Rainbow’ or ‘Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing In The Shadow?’ but they hadn’t done anything like ‘Eleanor Rigby’, ‘A Day In The Life’ or ‘Hey Jude’ to that point.

In late November, the band had headed back into the studio to start work on their next album, which would become Let It Bleed. In actuality, most of the album wouldn’t be laid down until February 1969. Still, they did record one song before the end of the year that ended up on the album, no doubt with “Na na na nananana” still ringing in Jagger’s ears.

For all the critical acclaim that the album as a whole gets, it is topped and tailed by two of the band’s most famous and critically acclaimed songs. It is possible that ‘Gimmie Shelter’ and ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want’ are among the greatest first and last track combinations on any album.

Jagger commented on the song's beginnings;

‘You Can't Always Get What You Want’ was something I just played on the acoustic guitar—one of those bedroom songs…. I'd also had this idea of having a choir, probably a gospel choir, on the track, but there wasn't one around at that point. Jack Nitzsche, or somebody, said that we could get the London Bach Choir and we said, "That will be a laugh”.

Laugh or otherwise, that is what happened; they didn’t quite go all out with a full orchestra like their Liverpudlian contemporaries did on ‘Hey Jude’, but the London Bach Choir opened the song, boosted the middle and brought it to an end. The music is flecked with french horns, Al Kooper’s piano and keyboards, and Rocky Dijon on tambourine, congas, and maracas. One notable change to personnel is that Drummer Charlie Watts couldn’t entirely lock down the rhythm that complemented the song, so producer Jimmy Miller2 filled in.

The tension in the subject matter is between wants and desires against needs. In his youth, guitarist Keith Richards was in a choir, much like the one in this song. When his voice broke in his early teens, he was kicked out of the ensemble. In his autobiography LIFE, he says that being in the choir may have been what he wanted but being in The Rolling Stones was what he needed. Many people growing up seek fame and fortune as aspirations but find, in later life, that a loving family and good friends are what gave them the happiness they were looking for. I can’t not mention that there is a distinct Hallmark greeting card to the lyrics when you read them on paper, but the music's majesty is enough for us to let that slide.

We also can see the lyrical content in the context of it being late 1969. Although the song was first released in mid-1969 as the b-side to ‘Honky Tonk Women’, the album was delayed to December 1969 and had a decent shout of being the last truly great album of the decade.3 There are three verses, and they appear to tackle, in turn, love, politics and drugs - three of the key platforms of the decade’s counter-cultural revolution. Although the song doesn’t have a negative vibe, there is a sense of weariness as the decade starts to wind down, and the positivity at the start of each verse turns sour before the chorus moves us very much into pragmatism, not idealism.

There are many demarcations for the end of the 1960s that are not 31st Dec 1969. The marketing for Paul McCartney’s self-titled debut that announced the end of The Beatles in April 1970 or Jimi Hendrix’s death in September 1970 are outstanding nominations. The Rolling Stones’ Free Concert at Altamont perfectly showcased the dream going sour. In terms of songs, though, it is hard to look beyond ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want’ as an audio semi-colon on the decade. This sense of partial closure is also reflected in its usage in 1983’s The Big Chill.

The film’s soundtrack showcases songs from when Baby Boomers moved from childhood to adolescence, roughly 1963 to 1971. When the soundtrack was released, they could squeeze an extra four songs onto the CD version that couldn’t fit on the LP. That certainly feels symbolic of something, yet I can’t quite put my finger on it.

In the context of 2022, a modern remake would probably have a soundtrack consisting of Wilco, Beyonce, Arcade Fire, MGMT, Katy Perry, Outkast and The White Stripes. Rather than using YCAGWYW, it could use LCD Soundsystem’s ‘Someone Great’ at the funeral, as that would be the equivalent for characters who were almost two decades from leaving school today.

According to Setlist.fm, the song is The Rolling Stone’s 9th most played song in concerts and in 2004, Rolling Stone magazine named it the 101st greatest song of all time, a worthy accolade - in the history of popular music up to 2004 there were only 100 songs deemed more deserving than this one.

Ninety-two places ahead of it were The Beatles with ‘Hey Jude.’

In the UK, 9th if you count US releases.

Most likely, the "Mr Jimmy” in the lyrics though some other Jimmys, namely Jimmy Hutmaker, have staked a claim to that badge of honour.

With apologies to Fairport Convention’s Liege and Lief

Wow.... I'm new to your publication/emails/articles. This one is right in my wheel house of musical interest. I hope this era is typical for you all! Thanks.