They're doing nine-to-five and moaning And they don't want you succeeding when they've blown it

The Streets - 'Stay Positive' (Original Pirate Material - 2002)

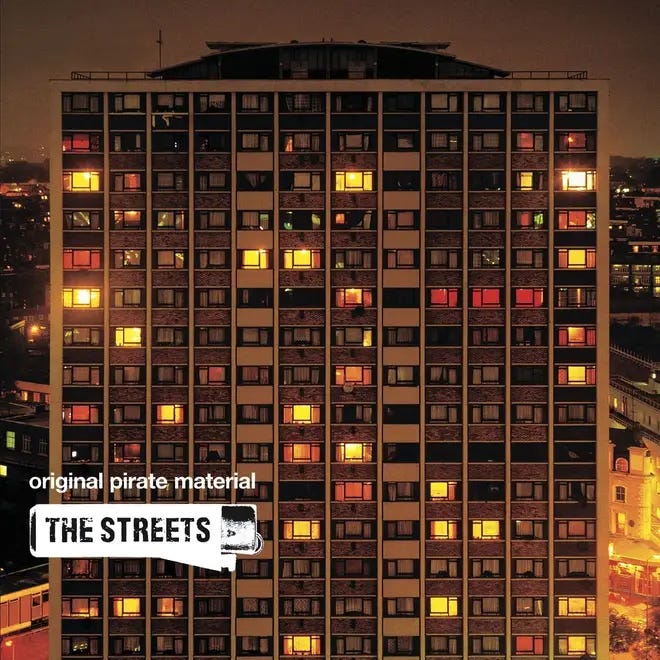

In 2001, Mike Skinner emerged from the underground1 with The Streets, bringing a distinct voice that would soon become synonymous with the documenting a new millennium's urban experience in Britain. His debut album, Original Pirate Material, felt like a breath of fresh air in a landscape dominated by polished pop, a handful of the Britpop war wounded and the first stirrings of those that hitched their wagon to The Strokes. I will be the first to admit that they aren’t for everyone but much like Richard Hawley would declare in 2007, for some of us, ‘Tonight The Streets Are Ours’.

For a few it was music that caught listeners’ attention, short of a Roots Manuva album or two that beans on toast, birds not bitches ethos was not something you heard from the missives sent over the Atlantic from Eminem and Dr. Dre, and why would you? Skinner told stories—simple, everyday stories—that resonated with people who could related to them. At the heart of this mission statement is the rallying cry at the end of the debut album, ‘Stay Positive’.

‘Stay Positive’ is quintessentially Streets. The song is built on minimalist beats, simple synth lines, and Skinner's trademark spoken-word delivery. This was a time when garage was not just a genre but a way of life for many, and Skinner, though not strictly a garage artist, was undeniably part of this scene. ‘Stay Positive’ is a reminder to hold on, to keep pushing forward despite the trials and tribulations that life throws at you.

The production of ‘Stay Positive’ is deliberately lo-fi, a choice that reflects the DIY ethic that was at the core of The Streets' identity. It’s not about grandiose orchestration or slick, polished beeps and boops; it’s about capturing raw energy and emotion of a moment. The sparse beats and echoing synths create a liminal space that allows Skinner's words to take centre stage. The message is simple, and yes maybe trite but sometimes the line between trite and profound depends on what mood you are in.

This ethos was particularly resonant in the early 2000s, a time when the optimism of the late '90s was giving way to a more cynical, harder-edged reality. The west’s long nineties were shattered by 9/11 and while the other side of the world The UK was coming down from the high of New Labour's initial euphoria. Skinner’s music was a reflection of this shift, a gritty counterpoint to the more polished, escapist pop that was dominating the charts.

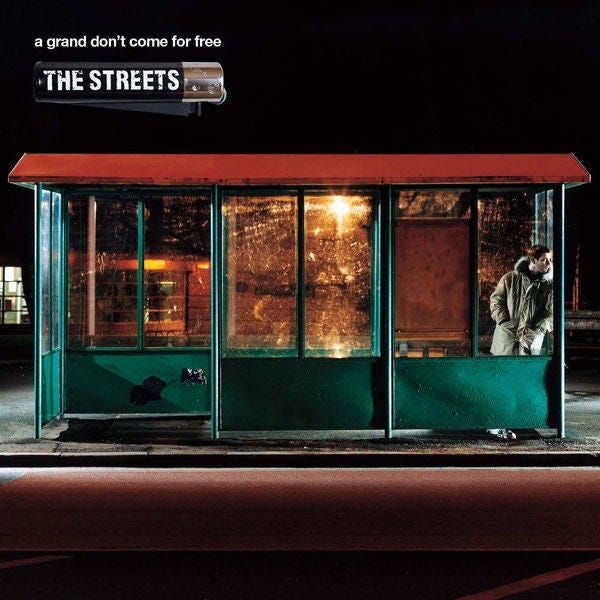

By 2004, when Skinner released A Grand Don’t Come for Free, he had firmly established himself as a unique voice in British music. If Mercury prize nominated Original Pirate Material was a snapshot of urban life, the follow-up was a full-length narrative, a concept album that followed a protagonist (essentially Skinner himself) through a series of personal misadventures. The closing track, ‘Empty Cans’, offers a resolution to the story that is both satisfying and unsatisfying - which in many ways is the album’s message about the unpredictability of the search for meaning.

I look down the back of the TV and that's where it was

The Run Out Grooves is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

So for the first time on The Run Our Grooves, let’s compare and contrast the two closing tracks. ‘Empty Cans’ is structurally and thematically more complex than ‘Stay Positive.’ The song is divided into two parts: In the first half of the track, the music is in a minor key, reflecting the despair and frustration of the protagonist's situation. After the narrative "rewind," where everything starts to go right, the music shifts to a major key. This change in tonality mirrors the change in the protagonist's fortunes, moving from a place of despair to one of hope and resolution. Again, some may find it corny, others will embrace it.

The production on ‘Empty Cans’ is more elaborate than on much of Original Pirate Material, featuring a fuller sound with a mix of organic and electronic elements. The strings and piano add a layer of melancholy that underscores the emotional weight of the song, while the beats keep it grounded in the urban reality that Skinner so vividly portrays.

One of the most memorable moments in ‘Empty Cans’ is the ridiculous reveal about the £1,000 falling down the back of the TV. It’s an absurd, almost surreal image that perfectly captures the frustration and futility of the protagonist’s situation. How likely is it that a thousand pounds could just disappear in to a TV like that? Even with the TV’s in people’s houses in 2004, it’s hard to imagine anyone seriously believing that such a sum could simply slip away behind a TV screen. But that’s exactly the point: the absurdity of the situation mirrors the absurdity of life itself, where things often go wrong for no apparent reason, and we’re left to pick up the pieces.

To understand the impact of The Streets, one must consider the cultural landscape of early/min 2000s Britain. This was a time when reality TV was beginning to dominate the airwaves, with shows like Big Brother and Pop Idol/X Factor offering a new kind of celebrity culture. Magazines like Zoo and Nuts were riding high, peddling a version of masculinity that was more laddish and often cruder and simplistic than that seen in Loaded and FHM in the years before. In a sense, Skinner’s music was an arm’s length and possibly ironic embrace of some aspects (cf ‘Fit By You Know It’) of what we refer to as Fiat 500/Deano lifestyle as well as offering a wry take for anyone else.

While he didn’t shy away from depicting the rough edges of life, there was always a sense of empathy and grounded humanity in his work that set it apart from the more cynical, sensationalist media of the time.

Skinner’s portrayal of British life was both specific and universal. His songs were filled with references to everyday experiences—waiting for the bus, arguing with your girlfriend, trying to make ends meet—that were instantly recognisable to anyone who had lived through or observed them. Yet, there was also something both zeitgeisty and yet unanchored to time about his work, a quality that has allowed it to endure far after the cultural moment that produced it has passed.

By the time A Grand Don’t Come for Free was released, Skinner was close to a household name, The album was a commercial success, topping the UK charts and spawning hit singles like ‘Dry Your Eyes’ and ‘Fit But You Know It’. But it also marked a turning point in Skinner’s career, as he began to grapple with the pressures of fame and the expectations that came with being considered as a chain in British pop storytelling lineage of Ray Davies, Paul Weller, Ian Drury, Billy Bragg, Jarvis Cocker and Damon Albarn but with beats as well as rhymes and melody.

The Streets were a product of their time, but their influence has been far-reaching. Skinner’s ability to blend humour and pathos, to find beauty in the mundane, and to capture the essence of a time and place made him a voice worth hearing. His work was deeply rooted in the specifics of British life, from the drudgery of 9-to-5 jobs to the escape offered by weekend raves and pub culture. But while his lyrics were often hyper-local, the emotions they conveyed were universal, resonating with audiences far beyond the UK. Skinner’s work remains a touchstone. When a young man from Birmingham could capture the hearts and minds of a generation with nothing more than a laptop, a microphone, and a keen eye for the details of everyday life.

Not literally.