Picture it. You are at a nightclub in any decent-sized town in the UK; it might be a 1980s bar like Reflex - but it doesn’t have to be. It could be at an Indie-leaning disco, any pub with a DJ on a random Friday night up and down the land - or at a wedding.1 There are handbags and temporarily discarded shoes on the dance floor if there is one, and the song has just reached this point in the second chorus

Don't you want me, baby?

Don't you want me…

The faders are switched down. It’s essential that this is done the second time and not the first because the first time, there isn’t enough tension crackling to be released in such a fashion. Everyone in the building goes, “Oh-oh-ohh!”.

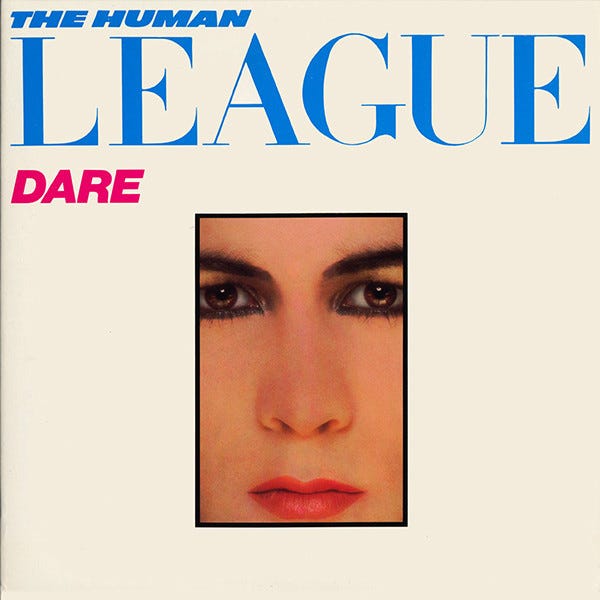

The song was Christmas number one in 1981, sold over 1.5m units in the UK,2 was a US chart-topper the following summer3 and is both one of the defining songs of the synth-pop era and has one of the most iconic music videos and opening lines of the last five decades.

So why am I writing about it as an album-closing track?

Phil Oakey, the lead singer of The Human League, had significant doubts about ‘Don't You Want Me’ and its potential success. He did not believe the track was of high quality and was initially against its release as a single for various reasons, including overkill as a fourth UK single and because it was too catchy. He’s on the record as calling it a poor-quality filler track with misgivings about Martin Rushent’s remixed version. The song was deliberately included at the album’s end to try and bury it. Virgin’s chief executive Simon Draper made the band release it as the fourth single anyway, compromising with Oakley that a poster would be included so fans wouldn’t feel “ripped off”.

The narrative of ‘Don't You Want Me’ is told from two perspectives—a man and a woman involved in a romantic relationship. The lyrical inspiration behind this story was drawn from a photo story in a teenage girl's magazine that Phil Oakey had read. In this particular story, Oakey was struck by the plot about a woman who achieves great success and, as a result, outgrows her older male lover. He thought it would make a compelling and relatable narrative for a song—especially if he could incorporate a unique twist.

While crafting the song, Oakey reflected this narrative through a male-female duet. The song opens with a male perspective, conveyed by Phil Oakey, who tells a story of a man who claims to have discovered and nurtured the talent of a cocktail waitress, turning her into a successful star and then lamenting the apparent end of the relationship, insisting that he was instrumental in the woman's success, we then get to the chorus where you can feel the desperation, affection and yearning her still has for her. He is pining for her like a recently deceased Norwegian Blue Parrot would do the fjords.

By switching to the other side of the story, sung by Susan Ann Sulley, we get the woman's perspective, contesting this claim and expressing her independence and autonomy. This twist is an intriguing dynamic for a pop song and is undoubtedly a significant aspect of the song's appeal, as is the affirmation that she can succeed with or without him.

More recently, In the years following the #MeToo movement, the song's narrative and lyrics have been reassessed by some. The lyrics depict a fraught and potentially manipulative relationship. While the song was initially viewed as a straightforward tale of a failed romance, some have interpreted these lines as representing a power dynamic that reflects broader societal issues of control and manipulation within relationships. We should note, though, that there is a strong female voice in the song, which asserts her independence and autonomy. Always has been.

Musically, ‘Don't You Want Me’ is a top-tier, defining track of the early 1980s synth-pop genre. The song starts with a catchy and iconic icy synth riff that sets the tone for the rest of the piece. This electronic motif is a prominent feature throughout the song, which many listeners associate most closely with the song. A bassline and rhythm tracks are played on a Roland System 100 synthesiser, with a sequenced melody produced using a Korg 700s. It is worth remembering that even with the nine-month delay until the US release, it was still the first song by a non-US act to top the charts featuring a synthesiser.

Producer Martin Rushent had a background in more conventional rock and pop. He played a critical role in helping The Human League transition towards a more pop-oriented sound while retaining the electronic elements integral to their identity. He used a combination of analogue synthesisers and digital sampling techniques to create a sound that was at once familiar and novel, bridging the gap between the band's avant-garde roots and the mainstream pop scene.

The composition also features a solid and clear rhythmic structure, with verse-chorus transitions that are both smooth and catchy. I love how the whole song ticks along like it is an electrocardiogram and the moment where the staccato percussion subtly shifts between “better change it back" and “or we will both be sorry” in the pre-chorus.

‘Don't You Want Me’ was a milestone in The Human League's ongoing evolution from their experimental electronic origins of the late 1970s to a more accessible, pop-oriented sound. This transition was not only reflective of the changes within the band but also a response to the shifting music scene around them.

The Human League were among the new wave of Sheffield-based bands in the late '70s and early '80s, deeply influenced by German electronic pioneers Kraftwerk. Bands like Cabaret Voltaire, Clock DVA, and ABC, among others, were all part of a "Sheffield Sound". This musical movement strongly emphasised electronic instrumentation, minimalistic arrangements, and a DIY ethos often involving homemade or repurposed equipment. Kraftwerk’s highly influential electronic sound and aesthetic were pivotal in shaping this scene.

In their early years, The Human League's music was much more experimental and abstract, closely aligning with Kraftwerk's innovative electronic style. However, the band's musical direction shifted with the departure of founding members Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh in 1980. While it is relatively easy to imagine early Human League material being played by the German band, it is far harder to imagine them mixing their cool, mechanised electronic instruments with the warmth of a female vocal as that of Susan Ann Sulley.

There’s a reason why you’ve never been in a nightclub listening to a DJ pull down the faders on ‘Radioactivity’ so that drunk women with stilettos in their hands can roar back “Discovered by Madame Curie” at the top of their lungs.

It could have been at my wedding, where this song was one of the many I had requested towards the night’s end.

It is in the top 30 of the all-time list of best-selling UK singles.

Placing it in the top 200 selling singles of all time in the US.

Quite probably my most 'worn out' vinyl album!

I really lucked out being at university in Sheffield from '79 to '82, such a great music scene and all the best punk/new wave bands playing at the legendary Limit Club (where Mr Oakey was a regular attendee).

In addition to the other Sheffield bands (of the time) you reference I'd recommend checking out: 2.3 ('All Time Low'), Artery, They Must Be Russians (named after a 'disgusted' letter to The Sun complaining about Punk), and, best of all, the mighty Vendino Pact.

Although it's not the best single, or even the best track on DARE, it says a lot about the songwriting quality of Oakey and co at that point that they could write a track of that calibre and dismiss it , and struggle to follow it up.