Please Do Not Adjust Your Set

How Boards of Canada end an album.

In a deviation from my standard rule of one post per song,1 I have been working on the concept of cluster essays, in which I look at an artist, a year, a genre or something that connects, binds or differentiates songs. Here is the first one on Scottish proto-hauntologists, brothers Mike Sandison and Marcus Eoin, aka Boards of Canada.

Boards of Canada have a particular way of signing off. Where most artists say goodbye, a closing track usually resolves tension, lifts or lowers the mood, or hints at what comes next. Albums by Boards of Canada end like the end of a broadcast day in Britain’s analogue TV days. In that sense, they don’t switch off, they power down.

It is a clock showing some ghastly hour in the morning, which is technically last night. A soft voice over a test card that precedes the National Anthem and four hours of silence before the return of life, and the saxophone-backed pages from Ceefax. Whatever mood the preceding tracks set, the closing gesture is deliberate. You can trace how these endings bind their catalogue together, even as the tone shifts from childhood warmth, through uneasy transmission and sun-bleached drift, to civil-defence chill.

Let’s start with Music Has the Right to Children2, released in 1998, just as the sound of dial-up modems began to get louder and louder. Closing track ‘One Very Important Thought’ is over a minute of a woman softly intoning in public-service style advice about free speech and censorship, accompanied by little more than a soft synth line. The album is over an hour of disassociation with a mix of half-remembered playground chants and woozy melodies. The whole record has an air of VHS hiss, though it wasn’t quite as retro as it seems now. In 1998, VHS was still the dominant, contemporary format. Even in 2001, Shrek sold over 2 million copies in the UK on VHS, with DVDs at around 700k. It wouldn’t be until 2004 that DVDs had the largest market share.

Rather than ending with a moment, a reprise, a nice little bow, the album ends with what passes as a continuity announcement, giving the record the air of a recovered lost library document, like a 1960s Doctor Who episode found in someone’s loft.

With Geogaddi (2002), we move from the “end of transmission” trope of continuity announcements to another characteristic. Silence. The last listed track, ‘Magic Window’, is almost two minutes of silence. Its length allows the record to reach 66 minutes and 6 seconds, a numerical joke with satanic and occult undertones. On the journey there, we have the audible dread in ‘You Could Feel the Sky’ and the more serene ‘Corsair’ as the mood ebbs and flows before we get to this numeric gag.

You can say that this is all there is to ‘Magic Window’, some numerology to hit a certain length. It is a numerical gag, yes, but it also restores the broadcast hush, a literal ‘nothing’ that tells you the programme has ended. I think that having vinyl or CD listeners encounter the silence is an active choice, not as provocative as 4’33”, but it still emanates the vibe of leaving the television on once the programmes have finished.

Three years later, The Campfire Headphase closes with ‘Farewell Fire’. Shorn of drums, it slowly releases the lingering notes, faded down by hand rather than cut. It is almost as if you can hear the fingers on the faders. Where the album in full leans into guitar and a washed-out Americana, the ending lacks the cut to black effectiveness of Geogaddi, but it's hard not to reach for the metaphor of a campfire burning out as, layer by layer, the song exhausts itself. It is the white dot left on the screen as the magnetic field in the cathode ray tube collapses, like a white dwarf, burning brightly but with a diminished presence.

Tomorrow’s Harvest (2013) is their starkest ending. ‘Semena Mertvykh’, seeds of the dead, is a short, desolate throb, a nuclear wind over desolate ground. It is not a cheery “see you tomorrow” affirmation like the BBC suits' good-night wishes after the weather. It is more like a civil defence broadcast, the likes of which are unlikely to be repeated, about a very different, much bleaker type of weather.

What makes these endings feel so coherent across a fifteen-year arc isn’t that they all have the air of the early morning shutdown, though that helps; it is that they all have the fingerprints of Boards of Canada on them. The brothers are like archivists, with their vintage synths and samplers, their ageing consoles and their inclination to leave audio ghosts in the machine.

Technically, these ghosts have names: wow and flutter. In strict audio engineering terms, they are errors, mechanical failures where the speed of the playback device wavers, causing the pitch to drift. “Wow” is the slow, seasick groan of a warped record or a stretching belt, which sounds slower than you’d expect. “Flutter” is the rapid, underwater gargle of a capstan struggling against friction and going quicker than you’d expect. In the hands of Boards of Canada, they are not imperfections to be sanded off. They are the heart of their sound. By introducing the sound of decay into the baseline of what the music is, they are engaging with the idea that memory itself is fragile and that their melodies are lost before they’ve ever been found.

This aesthetic is written through the idea of Hauntology, like a stick of rock. A concept borrowed initially from Derrida, but adapted for music by critics like Mark Fisher, Hauntology explores how the culture of the past, specifically the optimistic, modernist futures promised in the 1970s, continues to haunt the present. It isn’t retro or nostalgic in a Peter Kay remembers Space Hoppers kind of way. It is the eerie sense of a future that was always just out of reach, and a past spooked by the spectre of the Yewtree wrong-uns, and a decade lost to oil and IMF crises, amidst public information films seen on a TV wheeled into a dusty classroom.

Coupled with this, they all have the characteristics of a lullaby, with those childlike melodies, but with just a couple of percentage points of wrongness that linger, unresolved. These final tracks are quieter than what went before; the transmission is winding down, rather than a band taking a bow.

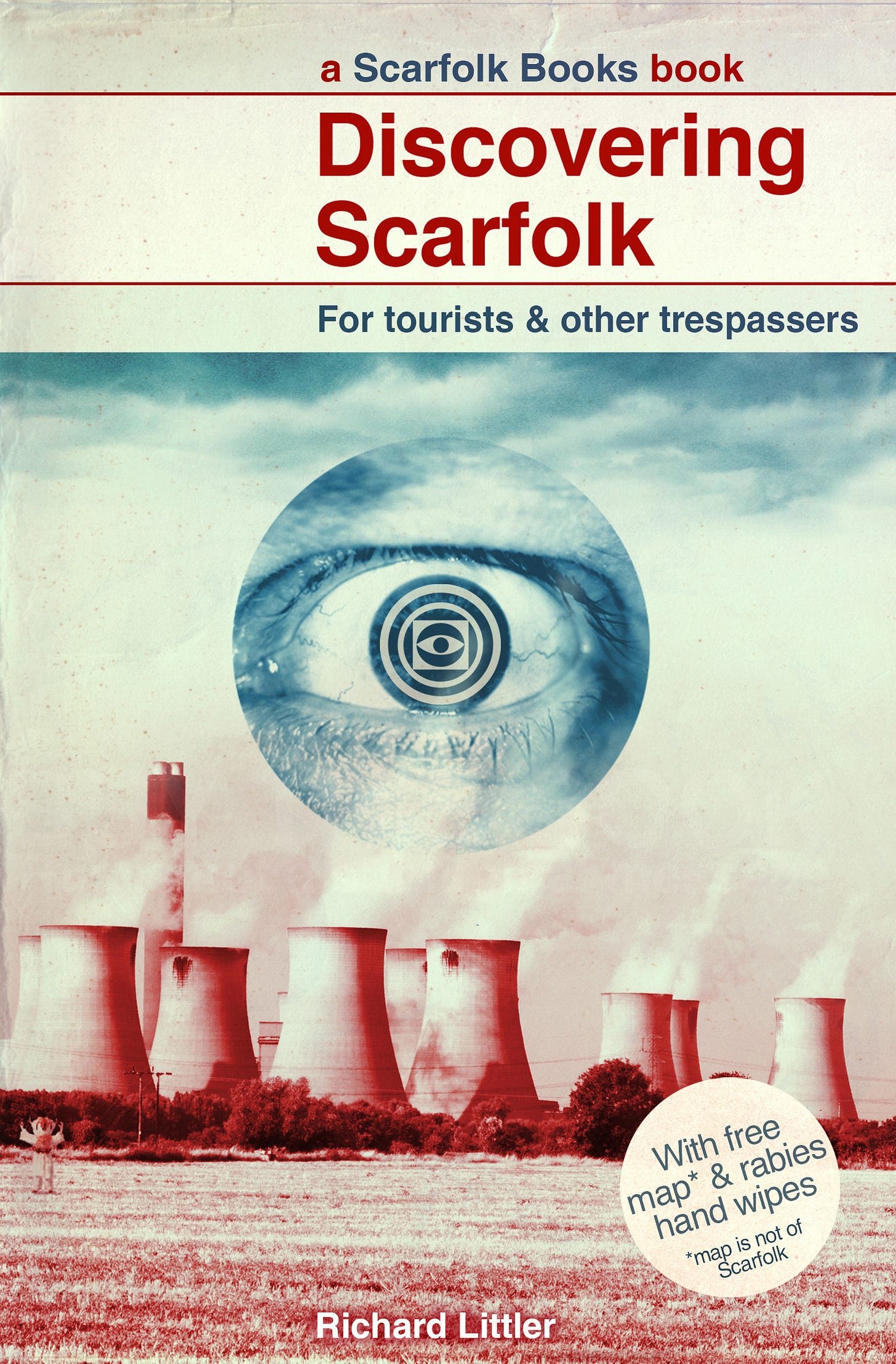

Culturally, their closers sit in a clear lineage. The palette is BBC Radiophonic Workshop, KPM and MusicHouse and schools programming. They inhabit a world where someone with received pronunciation tells you not to swim in a quarry or get your frisbee back from the electric substation. We see this, of course, played for laughs by the municipal, creeping terror of Scarfolk and the Auntie knows best comfort of Look Around You.

Other peers include the likes of Broadcast, who share the library-music DNA yet tend to favour torch-song melancholy rather than the institutional hush that Boards of Canada plump for. Burial, Aphex Twin and Autechre do textural endings, but they rarely feel like continuity announcements. The brothers often record to tape, re-sample to samplers, then re-record to tape again, baking wow and flutter into the signal so thoroughly that these power downs feel mechanical as well as emotional.

We should note that there is also a quiet wit running through these endings, even if they are played with a straighter bat than the Look Around You crew. ‘One Very Important Thought’ delivers a straight-faced PSA that also reads like a tongue-in-cheek legal disclaimer. ‘Magic Window’ is a literal window of silence with an album-wide number gag driving it. The humour is skeletal and deadpan, little more than a blink.

There is also the very particular feeling these endings unlock. They tap those liminal rituals that barely registered at the time yet are lodged in memory. The script is the same, only the intonation changes; courteous, warm, foreboding, or even wordless. These are records that partially resolve rather than pronounce a grand concept, and it is hard to imagine them closing any other way.

But now, from all of us here, this is The Run Out Grooves wishing you a very good night.

Except for the end-of-year round-ups, 2025 is just a few weeks away.

Many listeners remember the hidden ‘Happy Cycling’ on some editions, but the canonical sign-off is ‘One Very Important Thought’ from the original UK release.