I can’t argue with anyone who would insist that ‘The Winner Takes It All’ is the emotional peak of ABBA’s catalogue. Only ‘Dancing Queen’ trumps it on Acclaimed Music, and it sits ahead of ‘Waterloo’ and ‘S.O.S.’ there. So, in that sense, it is very fitting that their revolutionary digital concert, ABBA Voyage, finishes with a closing punch: the euphoria of ‘Dancing Queen’ followed by ‘The Winner Takes It All’ dashing you on the rocks. The song is grand, sweeping, cinematic, and profoundly intimate and personal. The melody, the emotion in the lyrics, and an ability to make the personal sound universal can all be found in the song.

The track itself is a study in controlled devastation, it walks away from you having delivered a punch to the gut. Released in 1980 as the lead single from Super Trouper, it quickly became one of ABBA’s most loved songs. The story is simple yet timeless: a relationship has ended, and one person (ostensibly the "loser"), is left to watch as the other moves on. Björn Ulvaeus, who wrote the lyrics, has always maintained that it wasn’t strictly autobiographical, despite its striking parallels to his own divorce from bandmate Agnetha Fältskog1. But regardless of its origins, the song’s power lies in its ability to speak to anyone who has ever felt left behind and the emotions that dredge up.

Musically, it is sparse. A slow, sweeping ballad built around piano chords and a soaring melody delivers a sense of resigned acceptance rather than outright anger. Agnetha’s vocal performance is fragile, and the ache perfectly matches the lyrics. But when the chorus arrives, she soars, pushing past heartbreak into something grander, more operatic, and cathartic.

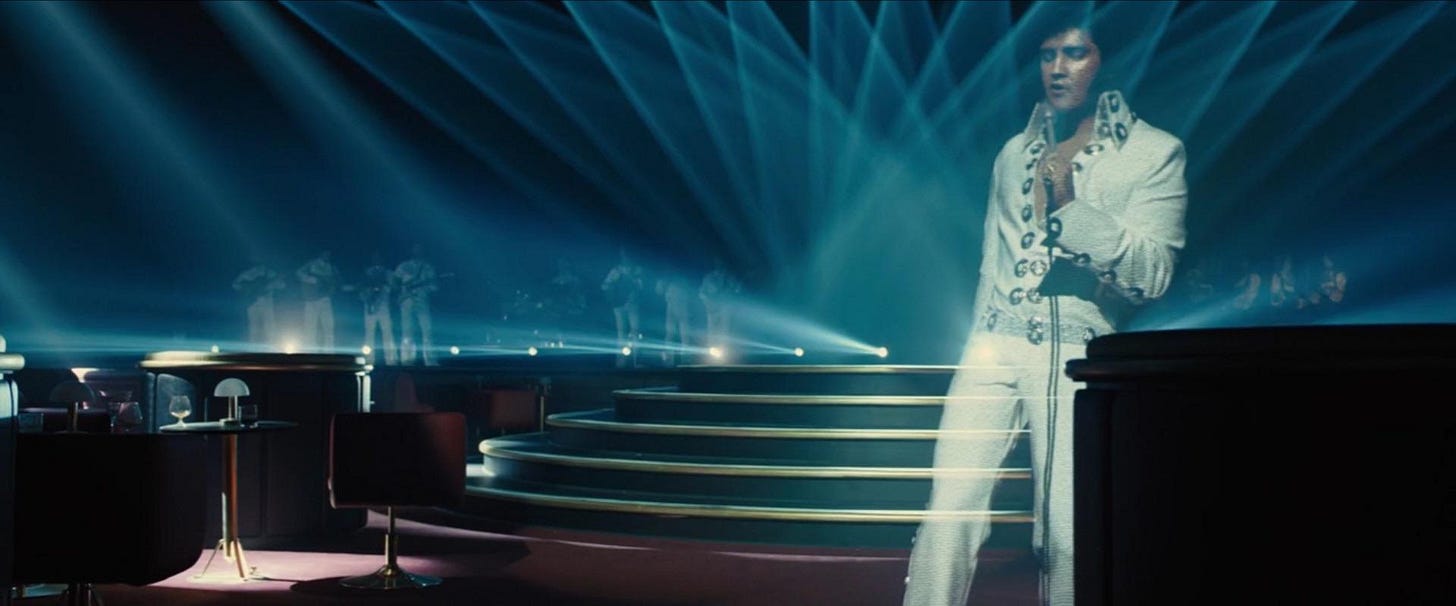

The show at the purpose-built ABBA Arena in London is a technological marvel, a concert without any of the band’s actual presence. Instead, digital avatars, meticulously crafted 1979 versions of Agnetha, Björn, Benny, and Anni-Frid in their prime, perform as if they were physically on stage, backed by a live band and dazzling production. The intriguing thing about the show is that the overall spectacle is such that many will forget that there are no visible life-size avatars for around 25% of the show. We see a backing band perform at a light and video show at those points. This does not seem to diminish anyone’s enjoyment.

The digital ABBA members are eerily lifelike, moving with an uncanny realism that allows the audience to suspend disbelief. The big screen versions of the “live” incarnations on the stage are projected at many times their actual size, like you would see at a real concert, and it lets you buy into the duplicity in front of your eyes. The concert setlist is packed with classics from their catalogue, but the playlist outside the venue also highlights that much is left off. ‘Super Trooper’, ‘One of Us’, ‘Take A Chance On Me’, ‘Money Money Money’ and ‘I Have A Dream’ all lay untouched by the pixels in the arena. I also found it an interesting choice for the live band (with Victoria Hesketh AKA Little Boots on keyboards and musical direction from one-third of the Klaxons, James Righton.) to be left to their own devices for the slightly questionable lyrics of ‘Does Your Mother Know?’

After the avatars deliver their encore, we see them return, but this time, they are in their 2020s incarnations rather than those of almost fifty years ago. ABBA have managed to pull off a reunion without stepping back on the stage again (it should be pointed out, the average age of an ABBA member is over 77, the time for any reunion was 25 years ago.) and in 2023 ABBA Voyage generated over £100 million attracting more than one million attendees to its virtual concert residency in London. The show saw a 97.8% occupancy rate, and 374 performances in 2023 - it also generated £1.4bn for the London and the broader economy, including inducing people to travel to London in the first place.

This raises a fascinating question: What is the future of live music? ABBA Voyage is more than just a nostalgia trip; it can be argued it is a time machine that runs in both directions, a glimpse into what concerts could look like in the coming decades. The technology behind it is ground-breaking, and while it currently works best with a band like ABBA, who have two lead singers, four members who were always somewhat theatrical and stylised, it’s easy to imagine other artists using similar technology.

For legacy acts, this could be a way to allow future generations to experience their music as if they were seeing them in their prime. Imagine a David Bowie experience or Prince concert recreated with the same level of detail, allowing audiences to experience what they never had the chance to. It also opens up possibilities for artists still alive but no longer touring. Could this be a solution for Kate Bush or Daft Punk? Could The Beatles perform as a full band once more, using a combination of archival footage and deepfake technology?

However, there are also ethical and philosophical concerns. Is a concert still a concert if the performers aren’t there? Does it change our connection to live music, or does it simply enhance it? ABBA Voyage arguably only works because it has the band’s full endorsement and involvement (Benny and Björn were directly involved in its creation). The avatars were designed using motion-capture performances from the band members themselves. But could we reach a point where such concerts happen without an artist’s consent, where estates and corporations control performances of artists long gone? Another clear issue is that since the 2000s the live music industry has been a key weapon in the music industry fighting back against declining sales of recorded music. As long as they are still able to manage it, we see many acts dominating arenas. Since it reopened in 2007 Wembley Stadium in London has seen 32 headline acts perform with the average release date of the artists’ debut2 being 1994 and only nine of the 32 acts younger than the new stadium and indeed 20 of them could have played in the old one3 and many did.

Those are questions for another time. Whatever you think ABBA Voyage is, it stands as one of those. A thrilling experiment, a show that bridges the past and the future in a way that no other live performance has yet or a dangerous harbinger of what is to come.

A demo is titled ‘The Story of My Life’.

Solo artists like Robbie Williams or Harry Styles are tied to their Take That and One Direction debuts.

This may have been a leap for Coldplay whose debut was released three months before the stadium shut for refurbishment.