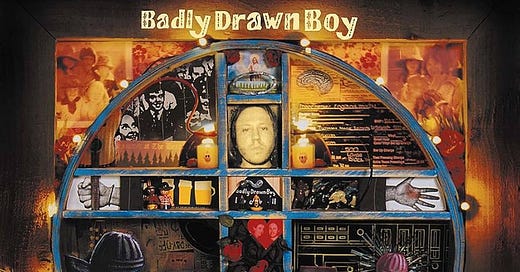

The closing track of Badly Drawn Boy’s acclaimed debut album, The Hour of Bewilderbeast, is aptly named 'Epitaph'. Sparse, gentle, and beautifully understated, the song feels like the quiet and solemn turning of a page at the end of a weighty chapter after an absorbing narrative. Damon Gough, the man beneath the knitted hat, gently intones a farewell, wrapped in more muted brass than can be found elsewhere on the record and gentle reflective piano chords. It’s a fittingly subtle conclusion to an album celebrated for its warmth, whimsical charm and kitchen-sink approach to melody.

Last month, I attended Badly Drawn Boy’s 25th-anniversary performance of Bewilderbeast in Southampton, a concert that felt as much like revisiting an old friend for a few drinks as it did marking a milestone. Hearing the record live, I was struck by how gracefully it has aged. While the audience warmly applauded every song and sang along with what counts as the hits from it, it was this understated finale that had me thinking about one of Southampton’s favourite sons, Craig David.

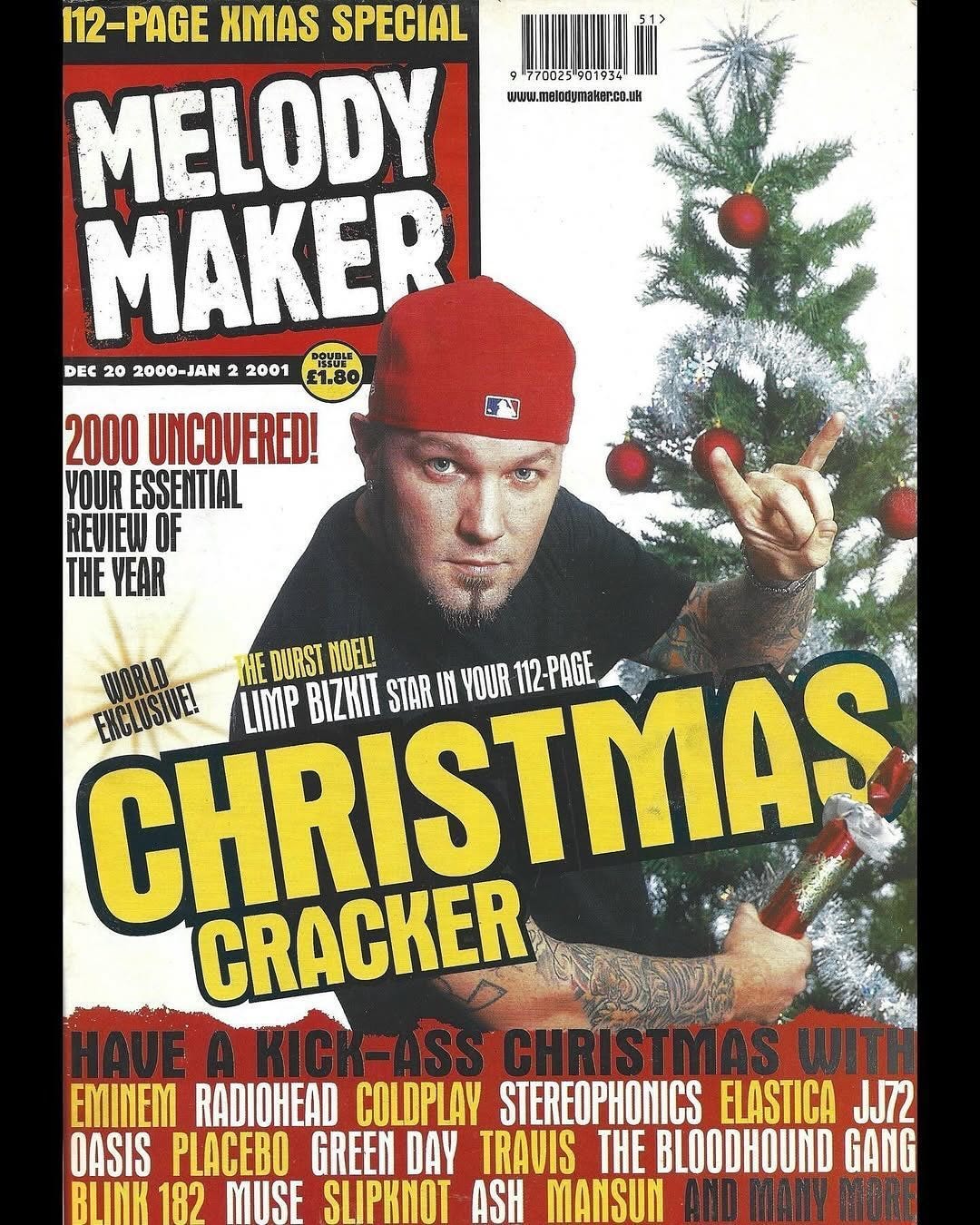

The term 'Epitaph' also feels particularly resonant when looking back at the state of British music journalism at that same point, 25 years ago. Especially Melody Maker, which ceased publication at the end of 2000. By then, the feverish highs of Britpop had cooled, and Melody Maker was faltering, overshadowed by its rival, NME. Dwindling circulation, identity crises, and an air of resignation characterised the final months of Melody Maker.

Unlike NME, which threw its weight enthusiastically behind scenes and trends, Melody Maker had long championed nuanced critique and artists who defied easy categorisation. Its demise marked the end of an era when multiple weekly publications defined cultural discourse in British music scenes. The loss of Melody Maker reduced critical plurality and foreshadowed the wider decline of print music journalism.

Reflecting on Melody Maker's twilight, its final months saw editorial confusion epitomised by its infamous October 2000 cover featuring a Craig David lookalike perched on a toilet, an unsubtle swipe at the burgeoning UK Garage scene. This was a misguided attempt to position itself against mainstream success stories that it really could have just ignored. As a sixteen-year-old going into year 12 at my school’s sixth form, I had endured and suffered enough from people who were fully signed up cultist followers of trance, house and now UK Garage music that actual adults listened to when they went out or to places like Ibiza and Ayia Napa. So I’m not going to pretend I was a big fan of Craig David or Artful Dodger or MJ Cole or Shanks and Bigfoot, etc.1 That didn’t really necessitate the toilet cover, though.

At the same time, the publication awkwardly endorsed nu-metal bands like Limp Bizkit and Papa Roach, or US hip-hop artists like Eminem and Outkast, genres outside its traditional guitar-centric comfort zone. While the likes of Neil Kulkarni can be found rhapsodising about Dilated Peoples in the pages, from an editorial point of view, any endorsements felt lukewarm and uncertain.

Ironically, the indie guitar bands emerging at the turn of the millennium, though pleasant, largely lacked the charisma or urgency that defined the Britpop generation before them. Acts like JJ72, Coldplay, Travis, and Embrace enjoyed moderate to actual chart success but lacked the distinctiveness or cultural bite that Melody Maker had historically championed. There were also simply not enough of them coming through for them all to be shared between Melody Maker and NME. These groups occupied an uncertain middle ground, neither capturing Britpop’s legacy nor pre-empting the indie revival led by bands like The Strokes, The White Stripes, and later, The Libertines, which the NME lashed to its mast. Melody Maker published its final issue that Christmas, the traditional double that spanned until 2nd January 2001 as the cover date. The Strokes released The Modern Age EP later that month and the magazine missed the chance to anticipate or support2 this revival.

That Southampton concert felt poignant through this lens, reminding me how cherished music remains intimately connected to the broader cultural ecosystem that nurtures and critiques it. I can’t help but tie back to Badly Drawn Boy to the other albums that have won the Mercury Prize like he did, I can’t help but associate it with Coldplay’s Parachutes, Turin Breaks’ Optimist LP and other records of that time like Travis, Doves, Kings of Convenience all covered in Tom Clayton’s 2021 book, When Quiet Was The New Loud. But I also associate it with other records from 2000 which opened my palette a little more as a sixteen year old fan of what we now call indie; Delgados, Grandaddy, Asian Dub Foundation, Lambchop, Yo La Tengo, Black Box Recorder and others made the leap off the pages into my ears via XFM 104.9, The Evening Session, John Peel or via MTV|2.

Revisiting the wider album and 'Epitaph' 25 years on, I felt gratitude for the cultural environment in which Gough’s album emerged, an era when critical plurality and deep engagement with music thrived, or it certainly felt like it did to me, which is maybe enough and all that anyone can ask for. Ultimately, what makes The Hour of Bewilderbeast so enduringly appealing is its strength as a ramshackle3 British response to Beck's Odelay, adopting an eclectic, charmingly haphazard approach to melody, genre, and instrumentation. It's a playful and quietly ambitious work that still resonates deeply with me, and a fittingly understated conclusion to a fascinating musical chapter.

Though even I couldn’t deny Sweet Female Attitude’s ‘Flowers’.

Or slam?

pun intended.

![The Hour of Bewilderbeast [VINYL] by Badly Drawn Boy: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl The Hour of Bewilderbeast [VINYL] by Badly Drawn Boy: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!hkRP!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0545681a-dc34-4719-b3b2-a742d43bcf41_894x894.jpeg)

Need to revisit this album, as it's been quite a while. I listened to it endlessly when it came out.