There were many possible epitaphs for Ian Curtis after he died. ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ was released a month afterwards and is the obvious one most people will know. ‘Atmosphere’ was released as a single in the UK that September and features prominently in 24 Hour Party People and Control. It was even played at Factory Records honcho Tony Wilson’s funeral in 2007. Deborah Curtis’s biography of her late husband, Touching From A Distance, takes its title from a line in ‘Transmission’.

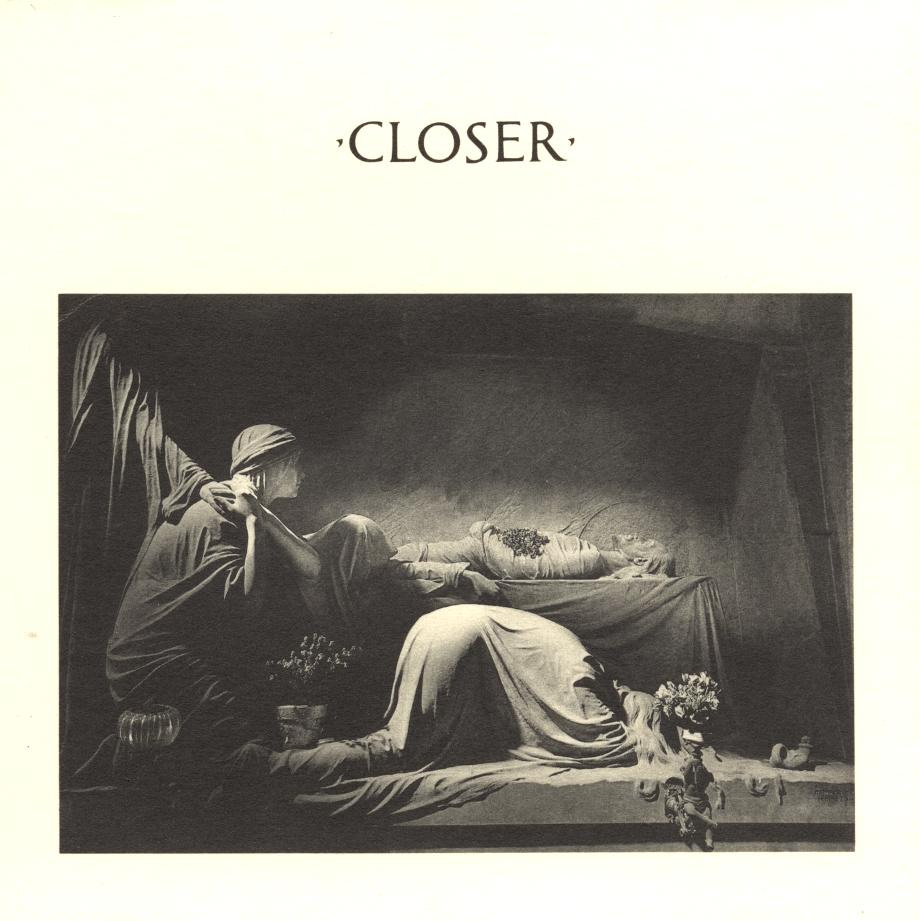

Two months after his death, the band released Closer, their second album and final studio album and bookend to the band’s career.

For many, this is a song about the impact of war on the generations of young men whom their leaders force to pick up arms and fight. As Paul Hardcastle informed us in 1985, in the Second World War, the average age of the combat soldier was 26; in Vietnam, he was 19. Curtis lays out the difficulties of adjustment to life once again as a civilian due to what was then called shell-shock but is now identified as PTSD.

That PTSD angle is interesting as some speculate that this is merely a metaphor and the song is about the band themselves1. Despite his relative youth, Curtis is coming to terms with the things that have defined his adult life - Joy Division, his young family and his disability. Potentially any or all of these could cause the weight on a young man’s shoulders.

A further theory takes the context of the whole album. On side one of the record, a man is contemplating his ultimate fate. On the album’s second half, which I genuinely think is the most vital Side B in the history of recorded music2, he steps through his death (“Existence, well, what does it matter”), the sorrow (“A cloud hangs over me, marks every move”), the elegy (“Procession moves on, the shouting is over”) and that leaves ‘Decades’ as a fast-forward to many years in the future to look back.

This is where the idea of Ian Curtis looking back at the impact of creative destruction will have the band’s trajectory and coming to the “It's better to burn out than to fade away” conclusion - I think this is a stretch. People read too much into the song and tie it to the ending of Curtis’s life. I believe that people take this too far and potentially ascribe meaning based on Curtis’s death to every uttered syllable on this record.

Away from the lyrics, the song is the slowest on the album - marginally slower than the preceding track ‘The Eternal’ and its funeral march pace but significantly slower than the other seven songs. The song has Bernard Sumner’s iciest synth use on the record and is almost peaceful and melodic if you discount the theme of youth fading through the protagonist’s fingers.

Coming back to Paul Hardcastle, I find the comparison interesting. The extended version of “19” ploughs a similar furrow on the loss of youth of the returning soldiers from Vietnam, their PTSD and readjustment to civilian life. The difference is it is backed with a pulsing synth-pop, Afrika Bambaataa influenced electro track - nothing like what ‘Decades’ sounds like, right? Except, ‘Decades’ was originally called ‘Euro pop.’

Drummer Stephen Morris told GQ in 20203;

It was originally called “Euro pop”, which it sounded absolutely nothing like. When it started it had a bossa nova beat to it, which Martin [Hannett, producer] absolutely hated. It was probably about the same day we would have done “The Eternal”. We didn’t have a drum machine at the time, so we hired one and this Roland CR-78. I’d never seen a drum machine before and thought Martin would know how it worked. He’s pressing buttons and it plays…. all those classic drum machine beats. I said, ‘Well it’s not really that kind of song, Martin. And he said, 'No. We can program it. They can make it play wherever you want.’

So there is this connection, where even on the last studio album by Joy Division, even in the months after Curtis ended his life, there are the seeds not just to ‘Ceremony’, ‘Everything’s Gone Green’ and Movement but to ‘Blue Monday’ and the rest of New Order’s discography. A back catalogue that opened up innovations in early techno house music and eventually gave artists who wanted to marry dance music and rock music their whole careers. Whether they were attacking it from one side or the other, the likes of The Chemical Brothers, LCD Soundsystem, Primal Scream, The Prodigy or Moby owe a considerable debt of gratitude, as does a sizeable chunk of the 1980’s popular culture to Joy Division’s attempts to incorporate the same drum machine that Blondie used on ‘Heart of Glass’ into their work.

The final minute or so of the song is a sinister, extended fade-out as Curtis asks of the young men “Where have they been?” supported by Peter Hook’s knotty bass-line and himself on the melodica, the lead singer doesn’t get an answer, steps back from the microphone and glides away.

This may be going too far - the song was initially titled ‘Cross of Iron,’ so there is a clear nod back to WWII, even if only when the song was in an embryonic state.

Someone who held a similar opinion was George Micheal. You can watch him talking about Closer in the context of the book An Ideal For Living being discussed on Eight Days A Week in 1984 with Morrissey and Tony Blackburn.

Closer’s release pre-dates the Phil Collins’ song by around 18 months, but the track that inspired a gorilla to learn the drums for chocolate does feature the same drum machine.