I’m delighted to bring you the first in ‘s guest posts on Nick Cave’s closing tracks - today, we have the first part of the 1980s; we will conclude that decade tomorrow, go through the 1990s, and come up-to-date over June and July.

With the admin done, I’ll pass the mic….

I never really saw eye to eye with the young Nick Cave.

Most of the music I love, from the revelatory punk revolution onwards, has strong elements of rebellion and anger right up front in the mix. So The Birthday Party should, theoretically, have been right up my street.

But the underlying message still needs a bit of melody to hit home effectively, and early Cave, for me, always seemed to dwell too long in the dark corners, its music too unrelentingly cacophonous, to avoid parking itself up a largely ignored cul-de-sac.

My good friend, and long-standing gig companion, Keith, reliably informs me, courtesy of his ultra-organised ‘concert list’ (which must now be fast approaching its fiftieth anniversary), that we saw The Birthday Party at Camden’s Electric Ballroom back in 1983 but, if so, this was an evening’s entertainment I can no longer recollect.

I am sure the young Nick would have been pleased, without showing it, if I had enjoyed his gig, but, with the Birthday Party ethos largely predicated on prompting a reaction, quite possibly even happier if I had hated it enough to recall my disdain to this day still. From Cave's perspective, having no memory of his band is likely the worst possible reaction (verging on contemptible).

So, with such discouraging, mutual first impressions, how can I possibly have ended up with a twenty-five-year (and counting) enduring relationship with The Bad Seeds? Well, the affair eventually blossomed (in a locationally appropriate setting) as I was driving over the Sydney Harbour Bridge on my way to work one morning in 1997.

With my car radio permanently tuned to Triple J, Australia’s excellent ‘alternative music’ station, the breakfast DJ announced an exclusive ‘first play’ of the new Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds single ‘Into My Arms’, and, as I passed the Opera House, I realised (with all the enthusiasm of a late convert) how much Nick had moved on since we lost touch. Somewhere along the way, Cave had discovered his melodic mojo.

Obviously, we had both changed a lot in the intervening fourteen years, but it still came as an unexpected epiphany to discover that Nick and I had finally found “some kind of path that we can walk down, me and you.”

All of which serves as a slightly meandering (as is my wont!) preamble to introduce the opportunity Mitchell’s The Run Out Grooves has kindly afforded me, over three monthly guest posts, to re-examine the entire catalogue of Bad Seeds studio albums.

My launch point may have been 1997’s The Boatman’s Call. Still, I have since travelled back in time, to an Orwellian 1984, to uncover From Her To Eternity (and everything in-between), and loyally journeyed forward with Nick, and his varying cast of Bad Seeds, right up to 2019’s Ghosteen (with much anticipation of more to come.)

And now, thanks to Mitchell, I have a chance to retread that ‘path’ by reassessing, through the ‘RoGs’ lens of their final tracks, each of the seventeen Bad Seeds studio outings (eighteen if you regard, as I’ve opted to, Abattoir Blues and The Lyre of Orpheus as separate, distinct albums).

A playlist with the six ‘closing tracks’ covered in ‘Act 1’ is attached below.

So, without further ado (eventually!), let’s start with the first sown Bad Seeds.

‘A Box for Black Paul’ - From Her to Eternity (1984)

“Ah’m enquirin’ on behalf of his soul.”

The Birthday Party ended, in suitable disorder, in Melbourne in 1983, after a final irreversible falling out (over songwriting differences) between Cave and his guitarist Roland S Howard, who later recorded some great work of his own, both with These Immortal Souls and over two solo albums.

Back in London, Cave quickly planted the Bad Seeds, replacing Howard on guitar with Einstürzende Neubauten’s Blixa Bargeld, adding Magazine’s Barry Adamson on bass, and enticing a temporarily lost Mick Harvey back into the fold’, with the band’s debut album From Her to Eternity surfacing in May 1984.

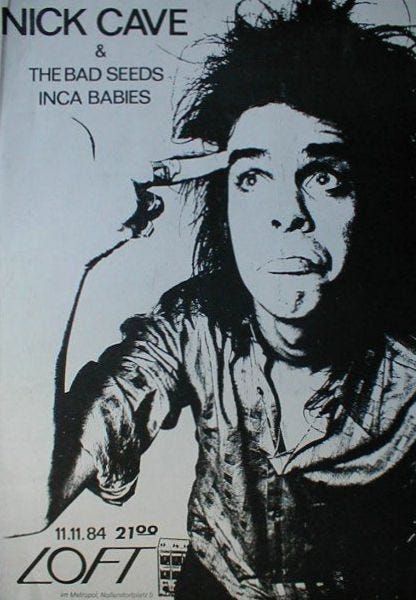

Despite the ‘statement’ name change and a reshuffling of the musician pack, it is clear from the outset this album is more evolution than revolution. Its opening track may be a version of ‘Avalanche’, with a faithful retreading of Leonard Cohen’s anguished lyrics, but this quickly becomes a cover whose musical accompaniment Leonard would struggle to recognise. There was still (as the tour poster below suggests) an unhealthy dose of Birthday Party (alongside other substances!) flowing through Cave’s veins.

A number of the following tracks continue this legacy feeling; with ‘Cabin Fever!’, ‘Saint Huck’, and ‘Wings off Flies’ all sounding like something straight out of the ‘Junkyard’. Familiar Cave vocal histrionics play out over typically untuneful noise; the cacophony even turned up to ‘industrial strength’ in places under Bargeld’s influence.

But every now and then (if you listen hard), there is an outbreak of melody, the merest hint of a tune poking its head above ground. I would argue the first nods toward a future Bad Seeds flowering come with the title track (and single) ‘From Her to Eternity’, and the following song, the album’s second cover version, a more reverential reading of Elvis Presley’s ‘In The Ghetto’.

The dedication to the discord of old remains in place for ‘From Her to Eternity’, but there are just a few indicators in the piano progression and choruses; Cave might be starting to acknowledge that a song doesn’t always need to be difficult to be worthy. And then, as if by magic, we get a pretty song. ‘In the Ghetto’, a fairly straight homage to (his hero) Elvis, marks a point where Nick finally seems to concede it might be OK to explore his singing (rather than ranting) voice. It would feel fitting somehow if (the ghost of) Presley ended up being just the inspiration Cave needed!

This all makes building ‘A Box for Black Paul’ a fitting finale, a neat summing up of this rather schizophrenic Bad Seeds debut. On the face of things, we are right back to another Cave painting of wilful obscurity; a Deep South-tinged lyric stuffed to the gunwales with indecipherable religious iconography. But, this time, the song’s sparser musical setting, based around a simple repetitious piano refrain, at least allows the storytelling (a later Bad Seed staple) to flicker, if not yet shine brightly.

This closing song (both its words and music) may be solely credited to Cave. Still, a noticeable tempering of the worst, least accessible Birthday Party excesses could perhaps be an early indication of the increasing influence, in a ‘musical director’ role, that Mick Harvey felt freer to wield within the band’s new incarnation.

As we continue revisiting these early Bad Seed ‘germination’ albums, there is further evidence of Harvey’s influence (as a force for good) becoming ever more important.

‘Blind Lemon Jefferson’ - The Firstborn is Dead (1985)

“Here come the Judgement train, git on board!”

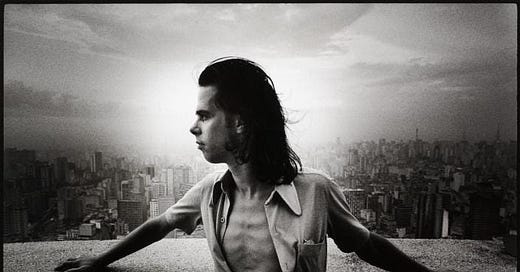

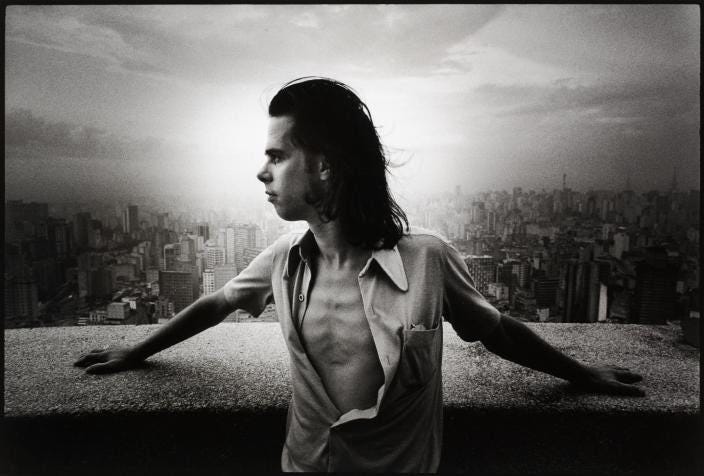

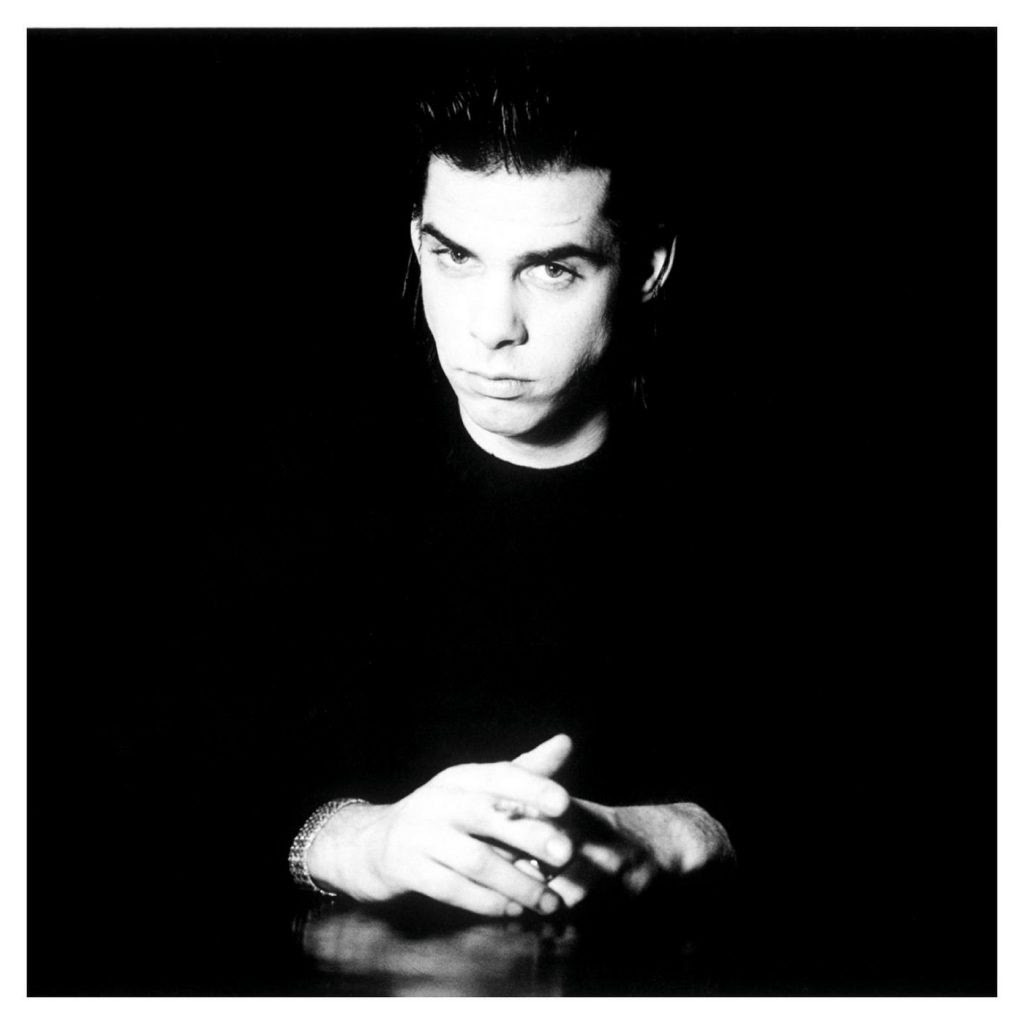

Sometimes a picture can say more than any number of words, so it goes with Bleddyn Butcher’s iconic photo of Nick Cave. One simple image tells so much about where the Bad Seeds found themselves as The Firstborn is Dead was released.

Geographically, the slimmed-down band (now just Cave, Harvey, Bargeld, and Adamson) had relocated to West Berlin, only to find their leader secluding himself away in his tiny garret room, predominantly focused on writing his first novel, a Deep South based, religiously tinged, Gothic tragedy called ‘And the Ass Saw the Angel’. The end result is a hugely ambitious story of unbridled (substance-fed) imagination, ultimately held back, in large parts, by verging on the unreadable!

So where did this leave The Bad Seeds? Theoretically, they were gathered in Hansa Studios to record their second album, but as Adamson remembers it;

the more Nick got involved with the book, the more he closed down.

With the novel’s mythic landscape and bedevilled imagery inevitably leaking over into Cave’s lyrics and the album’s songs mainly framed by the band’s offbeat take on a Mississippi Delta blues, this was never likely to become a breakthrough release.

It all starts promisingly enough, with a loud clap of thunder heralding ‘Tupelo’, Nick’s reimagining of the Presley birth story, depicting the King (Elvis Aaron) being born in a two-room shotgun house amid a biblically proportioned storm, arriving half an hour after his identical twin brother (Jesse Garon) was delivered stillborn.

It’s a heavy theme, which Cave cleverly insinuates, rather than belabours, and in doing so, achieves a birth of his own—the first appearance of a Bad Seeds’ classic. ‘Tupelo’ has since become a live set standard played over five hundred times (or so says Setlist.fm), developing a compelling momentum in its live setting it never quite achieves here.

It is always a problem, though, when the first track (the firstborn song!) stands above what follows, and ‘Tupelo’s wild storm overpowers the remainder of the album:

‘Say Goodbye to the Little Girl Tree’ - does at least take a break from the record’s otherwise unremitting anarchic blues, with a few good moments, but then

‘Train Long-Suffering’ (with a surely comic train whistle impersonation), ‘Black Crow King’ (which lyrically overplays the gothic imagery), and ‘Knockin’ on Joe’ (despite some nice vocal touches) flow into each other, with little else to comment upon beyond the latter being a death-row dry-run for ‘The Mercy Seat’, making

‘Wanted Man’, a Bob Dylan/Johnny Cash cover, the second most interesting song on the album as Nick intriguingly extends the original with new verses of his own.

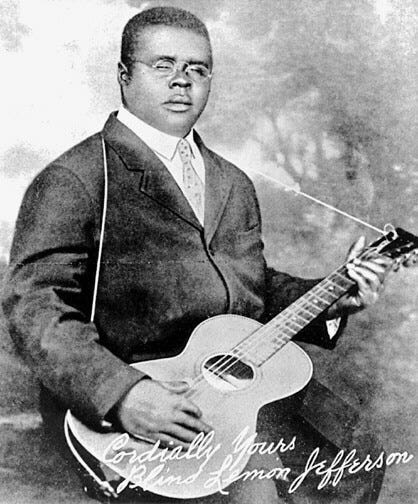

Which finally (before Mitchell prompts me!) brings us to the album’s run-out grooves. ‘Blind Lemon Jefferson’ bookends the record, as it started, with a tale inspired by another of Cave’s musical totems, this time the 1920’s ‘Father of the Texas Blues’.

Sadly however, if (as the song suggests) I were to, “git on board the Judgement train,” it would be hard not to conclude that Cave’s honourable intent to celebrate a largely forgotten, ground-breaking blues innovator isn’t matched in practice by this largely bland take (both lyrically and musically) on his source material. The lyrics may end with an exhortation, “let’s roll! yeah let’s roll!” but the song remains almost stationary.

I fear, like most listeners (even fans), I will be unlikely to return to The Firstborn … too often for anything other than ‘Tupelo’. At this stage, accessibility still seemed a game Nick Cave was reluctant to play, and re-listening to the album; it struck me the real hero here might well be Daniel Miller of Mute Records.

Thirty-eight years on, it is probably unthinkable now that any record label would ever have considered dropping Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, but with the group’s second album underperforming their first (not even cracking the album chart’s ‘top fifty’), you really couldn’t have blamed Daniel if the thought had started to cross his mind!

Yet Mute stuck with Cave and his band for another twelve albums (an act of faith that ultimately reaped rich rewards), helping guide them towards safer waters at the (still rebellious) outer reaches of stardom they continue to occupy today.

Where to go next must have been a valid question, though. Maybe it was time to crank out a few covers.

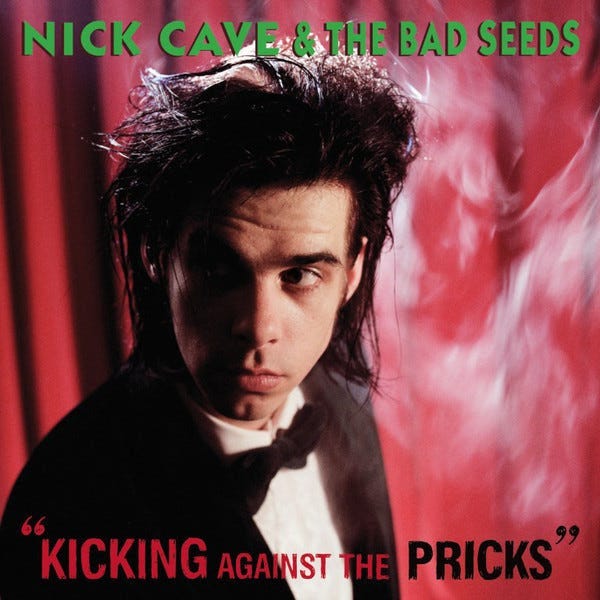

‘The Carnival is Over’ - Kicking Against the Pricks (1986)

“But the joys of love are fleeting.”

Whose idea was it to throw in an album of nothing but cover versions at this stage of a fledgling career?

Research seems to suggest it was Cave’s decision, though opinion is split on his motivation; it was either through necessity (as his novel had taken priority over songwriting) or bloody-minded vindictiveness, squarely aimed at his chosen archenemies, the music critics, who had largely panned The Firstborn is Dead.

Both the biblical quote chosen for the album’s title and an admission from Cave at the time seems to clear matters up.

It was basically a f*** you to all the people who thought they could tell us what we should and shouldn’t be doing.

Personally, I prefer to think of the whole project as the next stage of Mick Harvey’s Machiavellian master plan to gradually scatter The Bad Seeds onto less confrontational, more fertile ground. Wherever the idea came from, however, it seems an unarguable incongruity that the career of one of our most consummate, revered songwriters only really got into its stride on an album full of other people’s songs!

Contradictions aside, though, I have always been a big fan of cover versions.

Firstly, I think the choice of song(s) always tells you so much about an artist’s loves and influences, which is certainly the case here as Nick chooses to cover tracks by many of his musical heroes (Tom Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Cash, Lou Reed, Roy Orbison, Gene Pitney, and, perhaps most tellingly of all, Alex Harvey.)

And secondly, the discipline needed to pay suitable homage to the original song, yet stamping your own individual mark, often brings out the best in the coverers, helping point them in new directions of their own. Cave seemed to concur with this line of thought when he observed that the album, “allowed us to discover different elements, to actually make and perform a variety of different sorts of music successfully. I think that helped subsequent records tremendously.”

Following this logic, my favourite tracks on ‘Kicking Against the Pricks’ become the ones that move The Bad Seeds furthest out of their comfort zone by covering some of the ‘60s best known, epic pop ballads; ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix’, Something’s Gotten Hold of My Heart’, and, best of all, ‘Running Scared’.

It’s on the last of these where I think The Bad Seeds take their biggest step forward. Cave may never have the power or purity of voice of a Presley, Jones, or (in this instance) Orbison, but on ‘Running Scared’ he is forced into abandoning his previous reliance on ‘anger’ to employ a much wider range of emotions in his vocals. These may be baby steps, and you can still hear a sense of doubt in his abilities, but they give an early pointer towards the more complete vocal range Cave developed later.

This brings us very nicely, and happily with a little ‘joy’ this time, to the album’s closing track; as Cave himself explained it,

some of these songs had just kind of haunted my childhood, like ‘The Carnival is Over’, which I always loved.

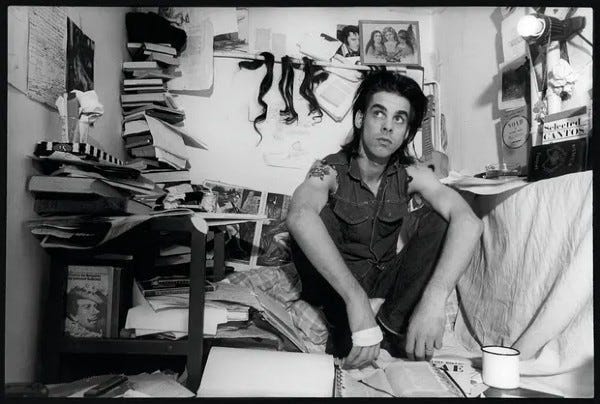

As a fellow child of the sixties (a little haunted by the image below), I know where he’s coming from.

This is probably one of the most faithful covers on ‘Kicking Against the Pricks’, with the Bad Seeds instrumental backing kept fairly sparse (although Blixa does manage to weave in a bit of subtle feedback guitar), but the reverence shown works. Nick might not manage to imbue “I will love you till I die” with quite the same degree of heartbreak as Judith Durham, and the remaining Bad Seeds were never going to match The Seekers in the harmonisation stakes, but as the music fades at the end, you are left with the same beautiful sense of yearning as the original—a great close.

Having re-listened to and reassessed the complete Bad Seeds back catalogue, this album marks a line in the sand, a point where the first wagons from the ‘carnival to come’ started to roll into town.

Come back tomorrow afternoon (UK time) for the second part of Tim’s look at the Cave/Bad Seeds closing tracks.

Just wanted to say thanks again Mitchell for this 'guest post' opportunity, it's an honour to join the Run Out Grooves ranks! I'm really looking forward to getting into the second batch of albums (Henry's Dream' through to 'Nocturama') which includes some of my all-time favourite Bad Seeds moments.

If anybody feels tempted (off the back of this) to give my 'maverick music' themed novel a try then the best place to catch up, from the start, is through the links on this post: https://challenge69.substack.com/p/a-chance-to-catch-up?utm_source=profile&utm_medium=reader2

Very excited for this series! Such a good idea. I think the best Bad Seeds album closer by some length is "Push the Sky Away", but would give honorable mention to "O Children" and "Babe, I'm on Fire." My sense at a quick scan is that he got better at album closers over time.