4,000 holes in Blackburn, Lancashire

The Beatles - 'A Day In The Life' (Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band - 1967)

It is always essential to have a sense of perspective when writing these. Some of the tracks we have looked at have been lightweight, and there’s very little written on them because there’s very little to write about.1 So, if I knew nothing about this next song, which would be tricky, some quotes about it would be pretty off-putting.

Walter Everett said in 1999;

Its mysterious and poetic approach to serious topics that come together in a larger, direct message to its listeners, an embodiment of the central ideal for which the Beatles stood: that a truly meaningful life can be had only when one is aware of one's self and one's surroundings and overcomes the status quo.

In his 1977 book The Beatles Forever, Nicholas Schaffner wrote;

Nothing quite like 'A Day in the Life' had been attempted before in so-called popular music. [the song’s] use of dynamics and tricks of rhythm, and of space and stereo effect, and its deft intermingling of scenes from dream, reality, and shades in between [It] was so visually evocative it seemed more like a film than a mere song. Except that the pictures were all in our heads.

More recent commentary from the likes of Paul Grushkin calls it “one of the most ambitious, influential, and groundbreaking works in pop music history.” John Covach says it is “perhaps one of the most important single tracks in the history of rock music”.

According to Acclaimed Music, it is the third-most celebrated song in popular music history. No pressure, then.

Back in early 1967, The Beatles had yet another whirlwind year which saw them record and release Revolver, ‘Paperback Writer’ / ’Rain’, George Harrison married Patti Boyd, The “Bigger than Jesus” interview, played gigs in Germany, toured Japan and Philippines,2 the US tour with the Bigger than Jesus fall out & controversy and at the end of the year back in Abbey Road to record 'Penny Lane' and 'Strawberry Fields Forever'. One crucial development not directly driven by them that year was The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds. This friendly rival moved both bands to more extraordinary artistic accomplishments with their music.

The sessions for ‘Penny Lane’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ had The Beatles thinking their next LP could be made up of a series of songs about their childhoods in Liverpool, those two songs had given them a start, but as 1966 became 1967, they were under pressure to provide two songs for an early single. They handed them over for release3, putting them back to square one and putting the idea of the childhood album to bed.

They began work on ‘A Day In The Life’ two days later.

It would be the first song, other than ‘When I’m Sixty-Four4’, that they had worked on in those sessions that would end up on Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which puts pay to the idea that the song was designed to be an epic closer to finish the record. In many ways, because of the reprise of the title track, it is more of an encore. It was certainly epic, ending up two minutes longer than anything they’d attempted to that point. It was also an LSD song in the vein of 1966’s efforts in the recording studio, such as ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, ‘Rain’, ‘And Your Bird Can Sing’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’.

A newspaper from 17 January 1967 set the ball rolling on Lennon’s lyrics. One story was around the custody ruling on the young children5 of the 21-year-old Guinness heir, Tara Browne, who died in a road traffic accident in December 1966. Browne was a friend to at least John Lennon and Paul McCartney and, according to Barry Miles’ book Many Years From Now, induced McCartney’s first LSD trip in 1966, so Browne aiding both songwriters with this song unwittingly is probably a realistic shout.

Lennon is quoted in Hunter Davies’s 1968 biography as saying of this section;

Tara didn't blow his mind out, but it was in my mind when I was writing that verse. The details of the accident in the song – not noticing traffic lights and a crowd forming at the scene – were similarly part of the fiction.

McCartney said in the late 1990s that he imagined a fictitious politician in a car accident, but Lennon may have had Browne in mind - in last year’s The Lyrics, McCartney is clearer6 that the car accident section is about Browne.

On another page in the same newspaper was a recycled local story about the state of roads in Blackburn. The original Lancashire Evening Telegraph piece had estimated that over a year, there was one hole for every 26 people in Blackburn. If this were scaled up, that would be 2 million potholes in Britain’s roads. These “4,000 holes in Blackburn, Lancashire” are then somewhat surreally7 able to fill the Royal Albert Hall8 in London.

In the song, another verse from Lennon talks of the English Army just winning the war, and the obvious reference here is the filming of Richard Lester's9 How I Won The War Lennon did in the autumn of 1966. I like the flip of the crowd gathering around the car accident in the first verse but turning away from the returning soldiers.10

McCartney’s verse fits in after Lennon’s around the English Army but before the potholes, but he did provide one crucial contribution to Lennon’s section. In a 1970 interview, Lennon explains;

Paul and I were definitely working together, especially on "A Day in the Life" ... The way we wrote a lot of the time: you'd write the good bit, the part that was easy, like "I read the news today" or whatever it was, then when you got stuck or whenever it got hard, instead of carrying on, you just drop it; then we would meet each other, and I would sing half, and he would be inspired to write the next bit and vice versa. He was a bit shy about it because I think he thought it's already a good song ... So we were doing it in his room with the piano. He said "Should we do this?" "Yeah, let's do that.

With Timothy Leary’s counterculture ideas and the phrase “Turn on, tune in, drop out” already making waves in 1966, it is clear that McCartney knew what he was doing when he added the line “I'd love to turn you on11”. Lennon again, this time in the 1980 Playboy interview;

Paul’s contribution was the beautiful little lick in the song ‘I’d love to turn you on.’ I had the bulk of the song and the words, but he contributed this little lick floating around in his head that he couldn’t use for anything. I thought it was a damn good piece of work.

As these sections from Lennon went from pen to recorded demos, McCartney also had his section, which eventually became the middle-eight, a slice-of-life vignette about riding the 82 bus to school - which would have tied in well with 'Penny Lane' as part of the now dropped Liverpool childhood idea for the album. Considering this section and Lennon’s on their own, you have his warm12, echoey, dreamlike vocals for a section about a transcendental, LSD-inspired disillusionment with reality contrasted with McCartney’s more mundane, routine-grounded in reality nostalgia for youth with its clipped and brisk phrasing. The song would be impressive enough if it were only these verses and the inventive piano and bass work from McCartney and Ringo Starr's never bettered drum work, rolling under the music like waves of distant thunder.

How they pieced it together was a work of stunning genius.

In between the Lennon and McCartney sections was an empty 24-bar gap. When recorded in January, this was counted out by Mal Evans; you can still hear him standing by the piano, barking out the number of bars elapsed on the final track. Once he got to 24, he set off an alarm. Some people have taken this to mean that an alarm was programmed to go off at that point - I’ve always assumed that he released the stopping mechanism on an alarm set to go off without it rather than set the timer. This works out perfectly if you imagine that Lennon’s section is a dream and an alarm clock snaps us into the real world where McCartney wakes up and falls out of bed.

10 February 1967 saw a bit of a party atmosphere in EMI’s Studio One at Abbey Road. Video footage makes it seem like a bit of a sixties “happening” in the room you had the likes of Donovan, Patti Boyd, Michael Nesmith, The Fool, as well as Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones and Marianne Faithfull. They were there as a 40-piece orchestra, many of whom had wacky pieces of flair like balloons, false noses and gorilla gloves, recording for the song. Both principal songwriters were interested in classical/avant-garde composers like Stockhausen and John Cage, so Lennon asked producer George Martin for "a tremendous build-up, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world" to fill that 24-bar gap.

In 1994’s All You Need is Ears: The Inside Personal Story of the Genius Who Created The Beatles, Martin explains his instructions;

What I did there was to write ... the lowest possible note for each of the instruments in the orchestra. At the end of the twenty-four bars, I wrote the highest note ... near a chord of E major. Then I put a squiggly line right through the twenty-four bars, with reference points to tell them roughly what note they should have reached during each bar ... Of course, they all looked at me as though I were completely mad.

Martin also said part of him worried about the orchestra being self-indulgent, but another thought it was “Bloody marvellous!”

McCartney wanted a 90-piece orchestra, but even a 40-piece orchestra was quite the raid on EMI’s coffers, £367 (over £8k in 2022 pounds), an absolute extravagance at the time. So they improvised by bringing in a second four-track machine, something that had never been done in a UK recording studio, to record multiple times, fill the additional machine and then overdub an enormous crescendo.

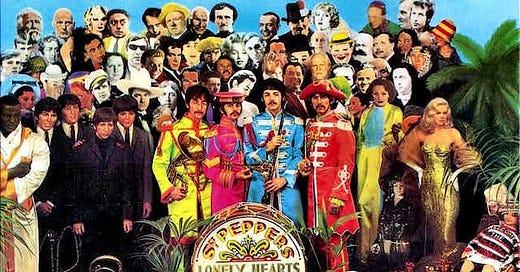

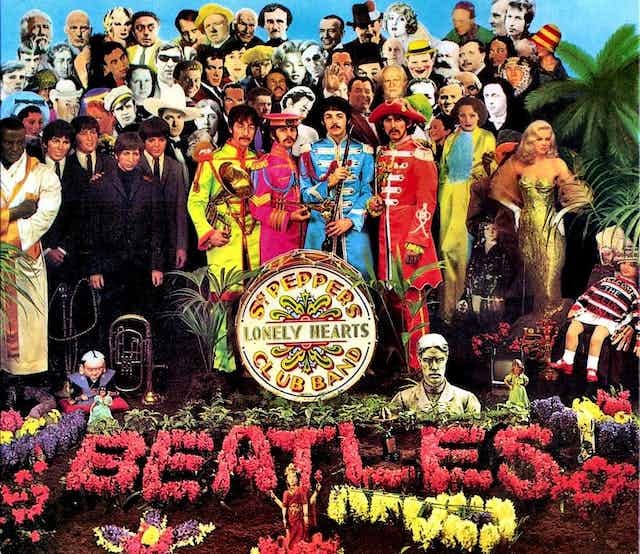

To close the song, the Beatles and the ensemble that night recorded a harmonised, Beach Boys-inspired vocal hummed chord13 but moved away from this idea and settled on what might become the most famous chord in popular music14. On 22 February, this time in EMI Studio Two, on three pianos and a harmonium, Evans, Martin, Lennon, McCartney, and Starr smashed down an E-major chord at the same time and let the sound ring out, the recording level was turned up and up and up for over 30 seconds so the chord could sustain at an audible level. In the Anthology series, this chord is accompanied by a shot of the Sgt Pepper cover filling in with colour, and as cliche as it sounds, many people will pick that chord as the moment that the black-and-white world of Britain, one only a dozen years away from rationing and post-war austerity, finally loosens the shackles.

Once that has faded, and we contractually have to mention it, the run out groove features a 15-kilohertz noise at the top end of the human hearing range and the same range as a literal dog whistle,15 followed by some gibbering which, on the initial pressing in the UK, loops infinitely.

I covered some of the commentaries on the track since 1967. More contemporaneously, a round of applause broke out after the orchestral passage was recorded, according to Mark Lewisohn. Lewisohn also says that present was Ron Richards, The Hollies producer and "[sat] with his head in his hands, saying 'I just can't believe it ... I give up.'" The total amount of time spent recording the five-and-a-half-minute-long song was 34 hours. In contrast, all 31 minutes and 59 seconds of the band’s debut, Please Please Me, were recorded in 15 hours 45 minutes on the same day, which equates to two minutes of recorded output per hour in the studio compared with under 10 seconds in the 1967 sessions.

While many people have acclaimed the song as one of the best album closers of all time, one of the best songs by The Beatles and one of the best of all time, not everyone was happy with the band’s direction. In a Beatle fan magazine in August 1967, Joanne Tremlett of Welling, Kent, said;

I was one of the first Beatle people in my neighbourhood to buy the new LP and I can’t tell you how disappointed I was when I played it through. Of all the songs, only ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ and ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’ itself come up to standard. Everything else is over our heads and The Beatles ought to stop being clever and give us tunes we can enjoy.

At this point, it was considered necessary to release non-album singles regularly.

McCartney had first written this song in 1956, aged 14.

The children’s mother, Browne’s girlfriend Suki Potier, was in the car crash that killed Browne but survived. She would appear in the film Wonderwall, soundtracked by George Harrison and the inspiration for the Oasis song. She would go on to be killed in 1981 with her boyfriend in another car crash in Portugal.

I think this is key to what Lennon is writing about, or at least his framing. The song isn’t about mundanity and boredom with everyday life but about the limits of perception. McCartney appearing to change his mind or misremembering the song’s genesis is very much in keeping with this.

Lennon couldn’t join the holes to The Royal Albert Hall until Terry Doran, a luxury car dealer and associate of Brian Epstein, suggested they could fill the Victorian venue.

The Royal Albert Hall is also about a mile away from the site of Tara Browne’s fatal crash.

Lester was the director of both A Hard Day’s Night and Help! before directing the second and third Christopher Reeve Superman films.

Almost certainly not what Lennon was thinking that early in the conflict, but a lack of a welcome home for many American soldiers returning from Vietnam has long been referenced as part of the poor treatment of veterans when they returned.

Predictably, these nods to drug usage got the song banned from BBC Radio until 1972.

You can also hear this at the end of the previous take one link.

It even has an influence on the film world, inspiring the Deep Note, the audio trademark for the THX film company.

Added at Lennon’s request. The Beatles’ sense of humour for you.

Great job Mitchell, there's been so much written about ADITL, but you managed to pique my interest all over again.

Just took another 'real' listen, and it is a truly groundbreaking song, not just for 1967, there are few bands in the intervening 55 years who've dared to be as experimental from a position of mass popularity.

Well done, Mitchell, on a tough task (as you acknowledged)! So much I didn't know, especially the actual construction of the song and final note (I trust you've heard The Rutles' parody, where a simple un-sustained one-piano-key note polishes off one sound-alike song). I was especially watching for any tip-o'-the-cap to the Beach Boys, and you did superb on that point, as well!!

Had to chime in, as I may be one of a very few who read this who not only was alive when the Beatles first appeared on US TV, but was 8, and sitting in rapt attention in front of the tube that fateful February '64 day! It's certainly not suffice to say it changed my life! I've been in search of the perfect riff ever since (as you might be able to guess from my writing, I'm a massive fan of Beatles 1.0 than Beatles 2.0, and the era represented by "SPLHCB," et al).

This'll be one of the few times I'll pull out my pop snobbery and ageism to say, "I'm glad my watching The Beatles on 'Ed Sullivan' wasn't simply relegated to just watching it on YouTube in the 21st century!" Hey, there's got to be SOMETHING to be said for being this old! Again, Mitchell, mad props, yo, for this writing victory!😁👍👏