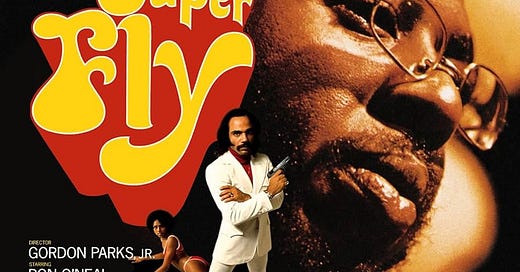

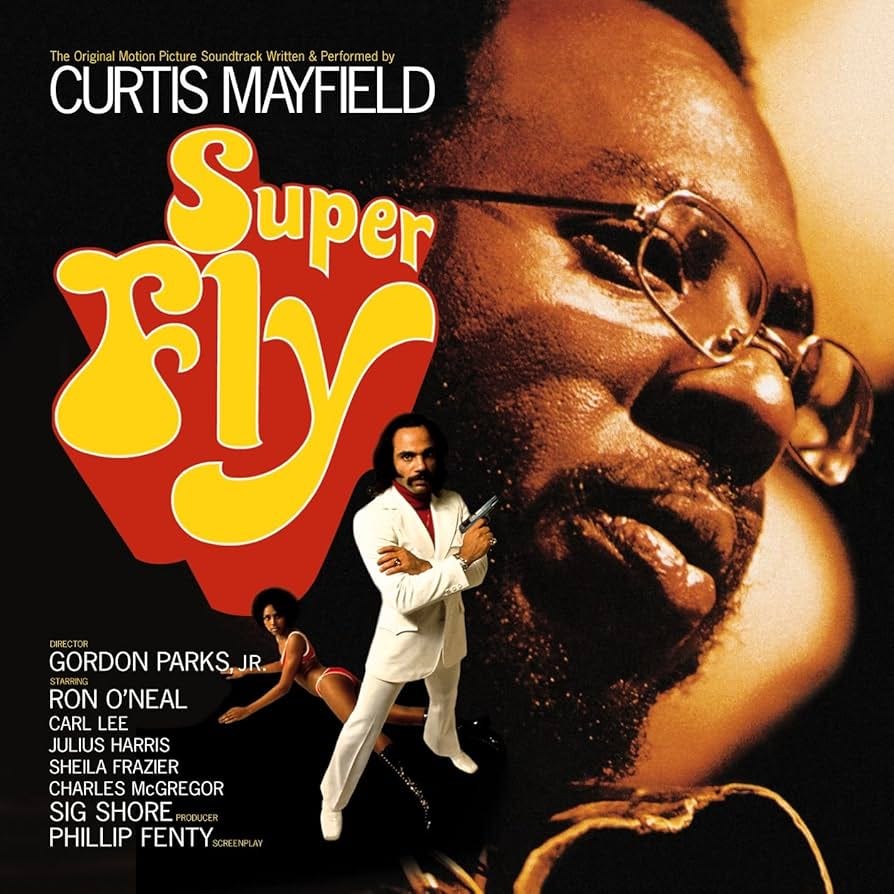

For me, Curtis Mayfield’s ‘Superfly’ is one of the landmark achievements in the annals of soul and funk music. As the closing track on the soundtrack album for the film Super Fly, it forms the culmination of Mayfield’s third studio album – an album that, against unbelievable odds, became the most commercially successful of his career. Record executives had little faith in its marketability, yet it resonated powerfully with audiences, turning the tide on scepticism in the industry. The track resonated with audiences and encapsulated a cultural moment that spoke to a generation of African Americans striving to reclaim dignity in an often oppressive urban environment.

The term “Superfly” itself is an expression with many connotations. As Mayfield once explained in Rapping with Curtis Mayfield (1972),

Superfly is an expression. It means many things. “Up”, “Hip”, all the high fashions, Cadillacs, Rolls Royce. Hip things that just might turn you on … Superfly.

Yet ‘Superfly’ was never intended to merely celebrate material excess. According to Traveling Soul: The Life of Curtis Mayfield, the song’s lyrics reflect not only the character of Priest, the film’s drug-dealing protagonist who defiantly declares at the movie’s close to the white deputy commissioner, “You don't own me, pig!”, but also mirror Mayfield’s own experiences growing up in one of America’s most segregated cities. His journey through the harsh realities of Jim Crow and the turbulent streets of the South provided him with the insight to write a song that was as much a personal statement as it was a reflection of a broader cultural struggle.

Mayfield’s production on the album was remarkably autonomous. He was granted complete creative freedom on the Super Fly project. This rare luxury allowed him to infuse each track with authenticity, and he was rewarded with the biggest hits of his solo career, from this closing title track to Freddie’s Dead, which made the US top ten.

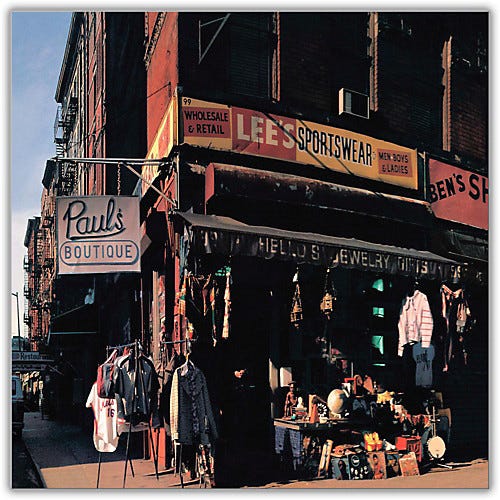

Musically, ‘Superfly’ is built on a foundation of minimal yet infectious grooves. The hypnotic and iconic bassline, played by Joseph “Lucky” Scott, and the distinctive rototom percussion break from Henry Gibson form the rhythmic core of the track. These elements have since been sampled on numerous occasions by artists spanning both hip-hop and pop, from the Beastie Boys’ ‘Egg Man’ on Paul’s Boutique to The Notorious B.I.G.’s ‘Intro’ from Ready to Die as well as Geto Boys, Alicia Keys and Space.

I shot a man in Brooklyn...

One of the curious elements of music criticism and analysis is that rock music has its own references and shorthand, which you really need to pick up and learn. If those references mean nothing to you nowadays, you can find those references by going to YouTube, Spotify or wherever.

The arrangement is spare and elegant, allowing Mayfield’s soulful vocals to ride over a soundscape that is epically cool yet pervades an air of contemplation. The song was originally an instrumental passage for the end of the film. After Priest’s impassioned stand against the oppressive deputy, the song plays over the closing credits, underscoring a moment of liberation.

As Mayfield later recalled to Q magazine,

It was a glorious moment for our people as blacks, Priest had a mind, he wanted to get out. For once, in spite of what he was doing, he got away. So there came 'Superfly' the song. He was trying to get over. We couldn't be so proud of him dealing coke or using coke, but at least the man had a mind and he wasn't just some ugly dead something in the streets after it was all over. He got out.

In both ‘Pusherman’ and ‘Superfly,’ Mayfield employs a staccato delivery that punctuates the lyrics with rhythmic precision, reinforcing the gritty, streetwise narrative. In ‘Pusherman,’ his crisp, syncopated phrasing mirrors the hard-hitting bassline and percussion, evoking a sense of urgency and defiance. ‘Superfly adopts a similar cadence; he sings them as Push.Er.Man and Sup.Er.Fly.

The cultural impact of ‘Superfly’ extends beyond the film. The song popularised the word “fly” as a descriptor of unusual and exceptional style - a term that would later find its way into the lexicon of late 1980s and early 1990s pop culture. References to “fly honeys” on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, dance troupes like the Fly Girls on In Living Color, and the casual query “Why you so fly?” in Tone-Loc’s ‘Funky Cold Medina’ all attest to the lasting influence of Mayfield’s work. His music, looking back, captured a sort of zeitgeist of a time when blaxploitation films were giving voice to underrepresented narratives and challenging the stereotypes that had long dominated Hollywood.

It should be recognised that ‘Superfly’ is not merely a snapshot of its time; it is a complex commentary on the multifaceted nature of urban life that existed both before and after. It reflects the struggles of an individual in a society rife with systemic injustice, yet it is imbued with a sense of determination and hope. For Curtis Mayfield, writing for a film steeped in the blaxploitation tradition meant engaging with themes of both glamour and grim reality, this approach that resonated deeply with those who saw themselves in the character of Priest. His music, rooted in the experiences of segregation and the fight for civil rights, spoke to the possibility of transcendence even in the face of overwhelming adversity.