We are building up a head of steam on the posts now, so would be great if you can keep sharing and subscribing

There are many universalities one can find in ‘I Shall be Released’; Spiritual, physical and emotional release, and it's certainly a song that I've caught myself getting wrapped up in during the winter lockdown the UK had for COVID-19 in early 2021.

'I Shall Be Released' is a Bob Dylan song written in the mid-sixties, and he eventually released it in 1971 on his 2nd greatest hits package with a different arrangement. It is probably the most famous of his songs recorded in the sessions known as The Basement Tapes, although it was not included on the 1975 official release. Instead, it arrived on the first volumes of The Bootleg Series in 1991, somewhat contradicting the key lyric that implores "Any day now, I shall be released."

This version by The Band was amongst the first official releases and is also closely associated with their final concert film, The Last Waltz, where it was the last song (despite not being the last song played at the gig). The song is also famous because of the many covers, including The Heptones, Peter, Paul & Mary, Joni Mitchell, Nina Simone, John Baez and Joe Cocker before 1970. The Beatles even played a jam version of it during their Let It Be sessions. Elvis, Jeff Buckley, Wilco & Fleet Foxes and Paul Weller would also tackle it over the next 50 years.

There are great swathes of analysis and much lore around the meanings of Dylan's lyrics across his back catalogue. Many of them are cryptic pieces of Dylanology about mules and binoculars. This song, like many The Band tackled from his songbook, is a lot more simple than cryptic and given its adoption as an anthem by the likes of Amnesty International, it would be hard to imagine the same happening with 'Visions of Johanna'

However, the imagery of being trapped features in both songs and 'All Along The Watchtower' from the same era. In fact, in 'Visions of Johanna', it is the concept of infinity on trial and trapped in a museum amongst the sprawling imagery.

The Band got there quicker than most for the finale of their debut album, Music From Big Pink. Fragile and haunted by melancholy, their version of a song that became a rousing closeout is cast as a down-tempo ending. Other covers don't have that coursing through them in the same way. I've never heard a version that implies so heavily through tone that any redemption has come too late to matter. It's a version that highlights the beautiful fragility of Richard Manuel's voice, and there is a wistfulness that adds to the air of poignancy.

The lyrics speak of being free and a man who has been framed, which recalls the question posed in The Shawshank Redemption of if and why Andy did it. Dylan himself has spoken of the release in the song as freedom from a body or from other's opinions, particularly of interest given that Dylan was feeling boxed in by the expectations of the folk community he had evolved away from in the middle of the decade. In reality, although there is a sense of time running out, especially in this version, and while we imagine a prison, the word is never mentioned in the lyrics. It might even be the second song on the album from the point of view of a dead protagonist after 'Long Black Veil.'

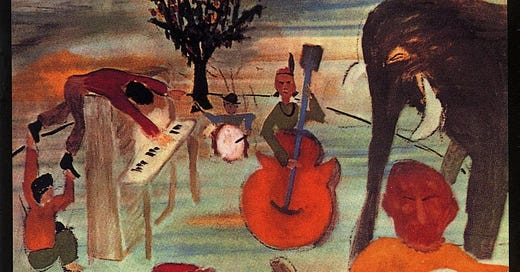

Because The Band recorded it a year before with Dylan and came back to it, they could add more of themselves to it. By the time of their second album, 1969's The Band, they are trying to pass themselves off as Confederate soldiers or cast members from The Grapes of Wrath and singing from a contemporaneous songbook. There is something ancient-sounding about the song, like it predates The Band, Dylan in the sixties and even the 20th century.

Interestingly, a song that pointed the way forward for The Band on their next album (Closers that suggest a way ahead for artists is a trope we will see a fair amount of in this Substack.) is so steeped in sounding like it was a 100-year-old folk also made a real impact on rock music? Take a look at a complete list of covers from the time. The album persuaded bands such as The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and others to bend away from the psychedelia of 1967 towards something more rustic. Eric Clapton quit Cream, and Led Zeppelin were never shy about indulging in their folksier nature on II, IV and especially III. You also have the emergence of bands like Creedence Clearwater Revival and Neil Young at the same time. I’d propose there's an argument that it is one of the most influential album closers in history of this type of rock music.